As our boat headed to the dive site, it was hard to imagine the previous year. With the island of Cozumel to my back, the 180-degree-view of water in front of me was filled with dive boats. While sometimes in the past I would be annoyed to see so many other divers, it was a relief to see all the boats, and it gave me a bit of hope for the future of the dive industry as the pandemic (hopefully) comes to an end. If it is open, they will come.

Contributed by

While tourism was way down throughout 2020 and the first half of 2021, from what I saw around me, it seemed to be making quite the comeback in Mexico. Dive boats were full, restaurants busy, taxis abundant. The first cruise ship returned during my week in Cozumel, and while there is a risk of too many divers and tourists causing harm or damage to the reefs and environment, Cozumel seems more than ready to get back at it, in the safest way possible.

In normal times, the popular dive location usually receives around 1.8 million tourists a year. While Cozumel is the largest Caribbean island in Mexico, it is only 48km (30mi) by 16km (10mi), and is located 81km (52mi) south of Cancun. In the past, the dive community and government have recognized that keeping the environment healthy is important not only to the planet, but to continued tourism, which brings in much of the island’s economy.

Back-rolling into the warm water, it was immediately evident why Cozumel is such a popular place to dive. A gentle current made it effortless to swim past the colorful reef, which seemed overgrown with huge sponges and sea fans, busy with fish. I saw yellow stingrays and flounders that were perfectly camouflaged in the sand.

Cozumel takes the protection of its reefs and environment seriously, and for good reason. Diving, snorkeling and fishing provide vital income and jobs for much of the island’s population, and the locals seem to understand that no reefs mean no tourists, which means no money. Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel (Cozumel Reefs National Park), established in 2006, covers most of the southern part of the island, consisting of around 12,000 hectares (29,600 acres) of sea and coastline. It is estimated over 105 coral and over 260 fish species can be found here. There is a daily fee (currently US$4.50) for those entering the park, which is used to support the national park system in Mexico.

The marine park’s rules prohibit:

- Standing or touching coral reefs

- Fishing, collecting or disturbing any marine organism

- Use of sunblock that is not biodegradable

- Gloves or knives

- Feeding any fish or animals

- Disposing of any waste or dumping fuel, oil or any liquid substance

Proactive guides

Throughout my week, I was impressed multiple times at how the dive guides not only preached the marine park’s rules and protection measures, but they also practiced them. I saw two separate incidences where divers were having some issues in the water, one falling into the bottom and the other kicking the reef. In other places, I have seen this happen, but the dive guide just goes on with the dive—maybe saying something back on the boat after the dive. But in both times this occurred in Cozumel, the dive guides of Salty Endeavors politely showed the diver what was wrong (cloud of sand, sinking, etc) and fixed the problem as soon as they saw it.

In one case, weight was removed (and carried by the dive guide for the rest of the dive), so that the diver was no longer overweighted and bouncing off the bottom. In the other case, the dive guide just pointing out to the diver his fins and where they were made the diver aware of his surroundings and stopped the issue. Back on the boat, the dive guides also talked with these divers in a way that impressed me, because it was not pretentious or scolding, but respectful, talking through what was going on and how to solve the problem. (I can recall other situations in the past when dive guides yelled at divers. Making someone feel bad usually does not help the problem, but only makes them mad, and they do not learn how to fix the problem, preventing issues from occurring again the next time). I was impressed.

Palancar Caves

On my second day of diving, we visited the beautiful Palancar Caves, which have lots of large coral structures and swim-throughs with bright orange tube sponges and deep maroon sea fans. A school of snappers were in formation as we swam under a coral ledge, and they hardly moved as we passed them. At another point, a hawksbill sea turtle was resting on a ledge, also unconcerned by our presence.

Toadfish

Our next dive was a shallow reef with a little less current. I had the splendid toadfish on my bucket list of fish to see. Thought to be endemic to the island, they have since been documented off Cancun and as far south as Honduras, but in Cozumel they were more common. As one of those “so-ugly-they-are-cute” animals; they have a wide, flat face with black and white zebra-like stripes. The fish peek out from burrows where the reef meets sand, and if you are lucky enough to see more of the toadfish’s oddly shaped body, you can see its fins stand out because they are bright yellow.

I had seen photos and heard there was a good chance to see them, but there are no guarantees in the ocean. However, on this dive, we saw at least seven! The only problem was I was shooting wide-angle with a fisheye lens, and although I took a few photos just for the sake of proof (and in case we did not see any more toadfish later), I knew the photos would not be top quality, because the fish is quite small. But it seemed like every few feet, our dive guide was pointing them out.

Photographic challenge

Planning to shoot macro the next day in hopes of seeing more toadfish, I did not even bother to look at my images until two days later. Back in my rental unit, I was zooming in and cropping quite a bit to bring the toadfish front and center, and saw something strange under the whiskery projections of the fish… they looked like baby toadfish! Knowing nothing about toadfish reproduction, I did a quick Google search and pulled up a few other images and a video showing how adult toadfish babysit their offspring until they are large enough to crawl out of their parent’s hole and go off on their own.

Super excited about this find, I sent Henry, Salty Endeavor’s owner, the photo to ask if this was common. It apparently was not, and he asked if I knew where we saw it. I did not remember. We had seen so many on that dive that I did not know which hole this photo was from. We went back the next day to look but did not find any with babies. But now I will look closer every time I see a toadfish.

This lucky find made me think about how the more we know about the ocean and marine behaviors, the more we can find (and the better photographers we can become). I knew enough to have an eye out for these awesome critters rarely seen anywhere but in Cozumel. However, I did not know enough to look for this special behavior, and it was only by accident that I got a very rough image of it. Now, I have something to go back for!

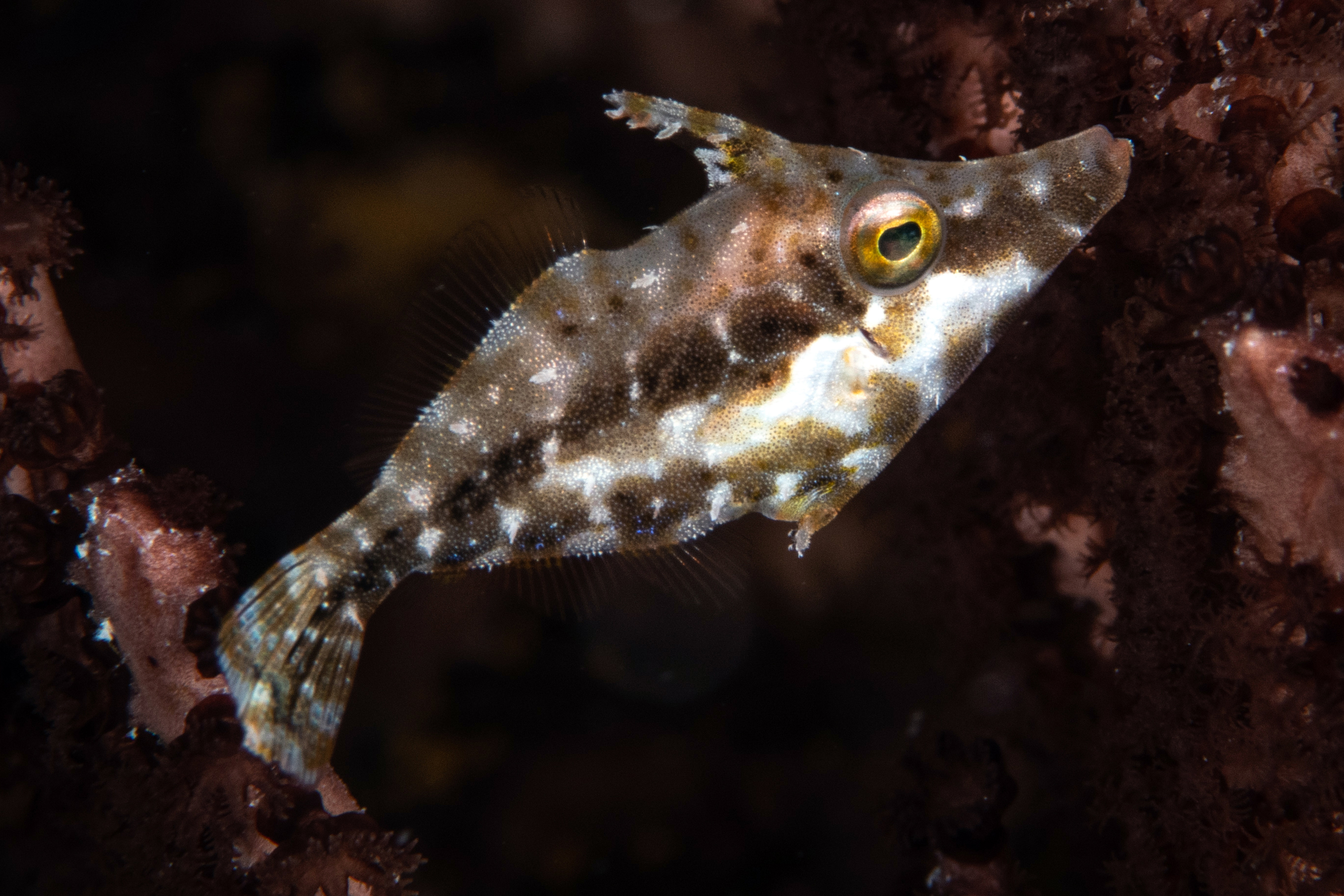

With macro lens ready the next day, I may not have seen baby toadfish, but we found plenty of macro critters. Flamingo tongues and arrow crabs were common. There were fairy basslets, slender filefish and the dive guide even pointed out a tiny painted elysia nudibranch (Thuridilla picta). We also saw several other toadfish, which were cool, even without babies.

Easy diving & dining

Not only was I enjoying the beauty of diving Cozumel, I also was enjoying the ease of it. Current is very common at most dive sites. While it can vary from day to day and from dive site to dive site, it is expected, and all dives are done as drift dives. The boat drives up to a great area of the reef, the divers get in the water, and they drift until it is time to come up. The boats follow the divers’ bubbles and the dive guide’s signal buoy, which is deployed on the safety stop, and then the boat picks up the divers wherever they end up.

Getting on the dive boat, also named Salty Endeavors, was easy too. It picked up passengers right on the resort docks of where they were staying or at the main town pier. I was staying in an apartment rental in town, so I met the boat at the town pier. Being close to the center of San Miguel de Cozumel, the main and largest town on the island was nice to visit for the variety of restaurants and the experience of walking around, checking things out.

I sampled a variety of the available dishes in town, including tacos, of course. But I also had some fantastic sushi, Italian and Indian cuisine, and I dined at several cute coffee-shop cafés with all-day breakfast options, healthy salads and sandwiches.

Glimpses of normalcy

At times, it felt surreal walking among other tourists, eating in restaurants and generally acting normal, as if the pandemic was a thing of the past. Masks were required unless eating or drinking, even outside while walking around, but that seemed a minor inconvenience to be able to travel again. We also wore them when boarding the dive boats, but soon after, they were removed because we were outside with lots of airflow on the boats.

Covid requirements

Covid requirements are changing constantly, but at the time of my trip in June 2021, no test or proof of vaccination was required to enter Mexico. Upon return to the United States, a negative Covid test was required within three days of flight departure, and it could be either an antigen or PCR test. I saw testing facilities throughout town, many offering 30-minute antigen tests. Many of the larger resorts had the ability to do testing on-site. There was also a mobile testing unit at the airport where you could get an antigen test before flying, by arriving at least three hours before flight departure (for a PCR test, more time was required).

On my last dive of the trip to Cozumel, I found myself almost in a trance of peacefulness. A slight drift made it so that I did not have to kick, and the water just moved me past the lovely reefs. It felt like a real-life nature documentary. I was relaxed, admiring so much beauty, feeling grateful both for the preservation efforts Cozumel has undertaken and for being underwater again to experience and enjoy it. ■

Thanks go to the dive center Salty Endeavors in Cozumel for their support and hospitality. For more information, visit: cozumelscuba.com

American underwater photographer, dive writer and regular contributor Brandi Mueller is a PADI IDC Staff Instructor and boat captain living in Micronesia. When she is not teaching scuba or driving boats, she is most happy traveling and being underwater with a camera. Mueller’s book, Airplane Graveyard, featuring her underwater photos of forgotten American WWII airplanes at the bottom of the Kwajalein Atoll lagoon, is available at Amazon.com. For more information, please visit: Brandiunderwater.com.