The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is undeniably the most well known of the ocean’s many predators. It has, one could say, “form” and is widely considered as a ruthless and terrifying man-eater, which has taken the lives of many innocent swimmers, surfers and divers.

Contributed by

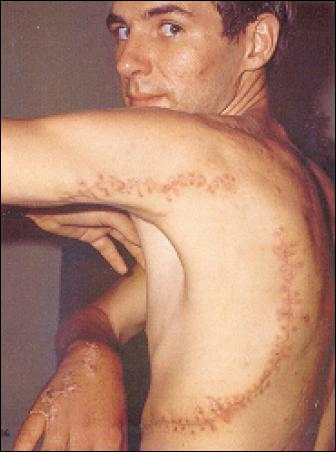

And, if you have anything more than a passing interest in these notorious creatures, you will almost certainly have heard of Rodney Fox—the man who miraculously endured a horrendous attack by a great white when he was spearfishing off Aldinga Beach, south of Adelaide, in 1963. To this day, nobody else in the world has survived such a ferocious attack.

The probability though is that even if you know about Rodney Fox and the attack, you may not know about what he did after he recovered from it, and how he became a staunch advocate for the protection of great white sharks, and the first to build a business that would actually take people to see them firsthand in the open water. It really is an amazing story and, on a personal level, one that helped inspire me to overcome my intense fear of sharks in general, and the great white in particular.

Over the years, I read everything I could about Rodney—so much so, that I felt like I actually knew him. Then, in November 2020, I finally got the chance to meet him—when he hosted a trip on board the new Rodney Fox expedition vessel to South Australia’s Neptune Islands as part of his 80th birthday celebrations. Rodney was on the boat for four days, and I was able to sit and chat with him for many hours about his life and adventures, which was just a wonderful experience!

On that trip, I also got to meet Rodney’s eldest son, Andrew, who has been running the whole operation after his dad retired back in 2000. You could say that Andrew is a hard read… He is a big guy with a commanding presence but does not say too much; however, when he does, it pays to listen. He also does a nice line, in rapier-like sarcasm, but beneath all that lurks a deeply knowledgeable and incredibly experienced expert on the great white shark. And not only that, his photographs of great white sharks are probably the very best in the world!

Born to sharks?

Imagine, if you will, growing up in a house where large and potentially dangerous sharks are part of the household fabric and where one of your earliest and most vivid memories is being woken up in the early hours of the morning to peer over the side of your dad’s abalone fishing boat to see the large head of a great white shark—spy-hopping, as it assessed the strange situation.

The boat, a 20ft-long half-cabin called Skippy, was there because Rodney had been contracted by Steve Spielberg’s production company to attract great white sharks for the live portion of the film Jaws. So, the Skippy was moored in Memory Cove, located southeast of Port Lincoln, while Rodney tested the reliability of the location and whale oil as an attractant. A seven-year-old Andrew had long gone to sleep in one of the bunks, and Rodney also eventually retired, only to be woken by a harsh rubbing sound along the outside of the fibreglass hull when the great white shark appeared!

Jaws made Rodney very much the go-to guy in South Australia for pioneering underwater cinematographers like Al Giddings and legendary National Geographic underwater photographer David Doubilet. Then came adventurers like Carl Roessler, Doug Seifert and Stan Waterman, leading well-heeled tour groups to experience one of the very extremes of the underwater world which, at the time, was almost akin to climbing Mount Everest. Then there were the shark researchers like Eugenie Clark and John McCosker, whom Rodney helped immensely in their quest to really understand the great white shark, rather than sensationalise the animal—not to mention, the iconic Australian underwater filmmakers Ron and Valerie Taylor who were a regular presence in South Australia.

Basically, Andrew’s formative years were spent with his dad receiving an almost constant stream of interesting, adventurous and extremely charismatic visitors—plus, Rodney took him on as many of those expeditions as he could. It was not your normal, everyday upbringing.

Being Rodney Fox’s son

Andrew is a really busy guy, but on a subsequent trip to the Neptune Islands, some six months later, he graciously agreed to sit and answer a series of questions I had put together, starting with, “What was it like growing up in South Australia as the son of Rodney Fox?”

Andrew’s response was that he just felt really lucky, because as the eldest son, he was the first to go out with his dad on the great white shark expeditions. Those were very much the early days of being in the water with the sharks, and there was much to learn, plus it was during a time in Australia that was significantly less regulated than it is now.

It was all incredibly exciting stuff, but because Andrew was completely immersed in it all, it was, as they say, just a “normal day.” He never really thought of his dad as being famous but did acknowledge that, at school, there was a degree of “tall poppy syndrome” expressed by the other kids, usually when there was something in the media about Rodney.

It was only as Andrew developed a sense of his own mortality in his thirties, that he fully realised what Rodney had gone through when he was attacked by a great white. He reckons that his dad just dealt with it all, both at the time and as he recovered, in the classic “she’ll-be-right-mate” Australian fashion and never really internalised the full magnitude of what had actually happened.

Career choices

Upon finishing high school, Andrew pursued a degree in environmental science at Adelaide’s Flinders University, which eventually gave him the pretty unique combination of an academic foundation, combined with unparalleled firsthand involvement with great white sharks. Although, he will admit it took him two years longer than it should have because of all the time he spent out at sea.

For me personally, one of the highlights of a great white shark trip on the Rodney Fox expedition vessel is the evening when Andrew does his “talk.” It is usually on the second night after everybody has settled in and is a very low-key affair—no egos on display. In fact, you get the distinct impression that he would much prefer it if somebody else was doing the gig.

But once he gets going, his deep passion and knowledge of the great white shark becomes apparent, and it is clear that Andrew is talking about his life’s work. There are, no doubt, other academics and researchers who know much more about key aspects of Carcharodon carcharias; but with over 40 years of empirical experience with these animals in South Australia and an academic foundation of his own, you quickly realise while listening to Andrew that the person standing in front of you is one of the world’s absolute experts.

The great white shark

Having spent so much time with these animals, I was intrigued as to how Andrew would actually describe them. His response was that great white sharks were “more majestic than menace, and still, to this day, so greatly misunderstood and holding on to their secrets.”

He went on to explain that while great white sharks are completely unpredictable and potentially extremely dangerous, their behaviour is driven by an instinctive capability to survive. And, as an apex predator, they do what they need to do when they need to do it—but with the ingrained caution and situational awareness that successful predation has taught them.

Much of that instinctive behaviour seems to be driven by how hungry they are—which is a function of when they last ate and what they ate. Based on a then ground-breaking US research paper (published in 1982), it was long believed that great white sharks can go for weeks before needing to feed. But a more recent paper by the University of Tasmania (UoT) indicates that they actually eat much more often. The difference between the two papers is that the first one used data from a tagged shark that was feeding on a dead fin whale, to calculate its metabolic rate and from that extrapolate how often it would need to eat.

In contrast, the premise of the UoT research was that the great white in the 1982 paper had already found an abundant source of food with the dead whale, and therefore, would have a low metabolic rate, as it leisurely worked at the “all-you-can-eat” buffet. So (with the help of Andrew Fox), the UoT researchers tagged sharks at the Neptune Islands, which were patrolling and actively hunting for seals. The findings showed that these sharks had a much higher metabolic rate and would therefore have to eat much more often.

The “Reader’s Digest” version of it all is that great white sharks need to eat every day when they are feeding on open-water fish like silver seabream. On the other hand, when they switch to fat-rich mammals around the Neptune Islands, consuming a seal every two to three days is probably enough.

The bottom line is that the urge to eat and the availability of suitable food is probably the major driver of behaviour, and great white sharks do need to eat quite often. How often is a function of the nutritional value of what they eat. Seals are highly nutritious, silver seabream less so but still adequate, while humans provide very little nutrition and are simply not on the shopping list!

Getting to know them

Andrew has personally identified around 1,000 sharks, mainly by using their unique markings and personalities. The pigmentation markings on great whites are very stable and stay with them as they grow—which is how sharks like “Pi” and “Heffalump” were first spotted and named. Then, there is the physical damage like the deep gouges on “Scarface,” or the deformity on “Imax,” and finally there is sheer physical size, as with “Mrs Moo.”

The Neptune Islands are a very important location on the great white “superhighway”—the migratory corridor the sharks use along the southern coast of Australia. The waypoints along this corridor are where the sharks know they can feed; and the seal colonies of the Neptune Islands, which are considered among the largest in the country, provide a known and reliable source of high-nutrition food. This is particularly so during winter and spring each year, when recently weaned seal pups are first venturing out into the open waters around the islands.

Some of those identified sharks appear there every year—such as Imax, who turns up like clockwork, mostly in winter. On the other hand, an individual named “UFO,” a 6m giant, made a reappearance at North Neptune Island after a 12-year gap.

Such reappearances are a cause for celebration, as Andrew observes how they have grown and how they are faring in general. But where they go remains an intriguing mystery, as they must be feeding somewhere else. Compounding that mystery is analysis of tissue samples taken from various sharks, which indicate a fairly wide variety of food sources. Meaning they have alternative feeding sites that are not seal colonies—but exactly where those sites are, nobody knows.

The ethics of it all

For the vast majority of underwater photographers and probably most scuba divers, cage diving with great white sharks is firmly on the proverbial “bucket list.” For me personally, it was something that equally scared but intrigued me, and my first trip to Port Lincoln back in 2003 was almost an out-of-body experience. It was also an experience that changed the trajectory of my life, as I realised that more than anything else I had tried, photographing big animals underwater was something I really wanted to do.

But whenever I talk to non-divers and underwater photographers about great white sharks, they are usually incredulous that I am so keen about it all. And, occasionally, I will encounter somebody who vehemently believes that it is completely wrong to conduct these “interactions.”

A common thread in these responses is that by encouraging potentially dangerous sharks such as great whites to interact with humans, we are changing their behaviour. And, in doing so, it greatly increases the chances of humans being attacked. So, as someone with probably more firsthand experience of those managed interactions than anybody else, I was very interested in Andrew’s opinion on this matter.

His main response was that great whites are very much apex predators and are able to do whatever they want, so very little that humans do, deliberately or inadvertently, has any impact on them at all. At the Neptune Islands, for example, great white sharks are present all year round—albeit, in greater numbers in winter and spring when the young seal pups offer relatively easy targets. But being present in the general area does not mean that the great white sharks will respond to the hurly-burly in the water and come to the boat.

Some do and some do not, and Andrew referred to Imax as a classic example. While Imax does come and check out the boat, this shark only appears when the “ocean-floor cage” is lowered and is never seen at the “surface cage.” Why? Well, nobody knows but Imax. And it seems that is just the way it is—which is something Andrew is very comfortable with, as the last thing he wants is for these magnificent creatures to behave like circus animals.

Over the years, the “attractants” used to get the sharks to the boat have evolved from the original “witches’ cauldron” (as it was nicknamed) of horsemeat and other such delicacies, to the minced fish that is used now. With the benefit of hindsight, Andrew makes the point that none of the attractants used was significantly better than any of the others, and at the end of the day, all of them are simply trying to get the sharks’ attention by stimulating their sensitivities.

When that works, it provides the trip participants with an opportunity to see firsthand an animal that relatively few others have seen. Almost without fail, this exposure leaves a deep, meaningful and positive impression on the diver, and Andrew believes that this is the case due to how they, as an operator, handle it—because sensationalising it all does not benefit the participants nor the sharks, he said.

High-adrenaline moments

With almost 40 years of cage-diving experience, I knew that Andrew must have had some high-adrenaline moments, and I managed to get him to talk about a few of them—which he did in a really down-to-earth and very casual fashion, further raising the high bar of my regard for him.

Andrew said his most memorable moment was during a trip he took to the Neptune Islands to test electronic shark repellents when, somewhat ironically, there was an unusually large number of sharks around the back of the boat—some of which were very dominant, with the other sharks clearly wary of them.

Underwater, in the ocean-floor cage, at a depth of 30m, a total of 19 sharks were counted and photo-identified, with 15 known and four new—all within a very hectic 15-minute time period, which was the best overall experience in all of Andrew’s years of diving with great white sharks. Bear in mind that three sharks around the ocean-floor cage at the same time is a big day. So, 19 sharks seemed like a veritable plague of locusts!

I was very curious if Andrew had ever been really scared, to which he said that bad weather in the Southern Ocean was always the thing that worried him the most as it can be really intimidating. In terms of outright, in-your-face “scary dangerous” moments with great whites, there was his experience with the individual named “Jumbo,” a 5m female that was a regular visitor to the Neptune Islands and a formidable, bold and intimidating great white shark. When Jumbo appeared, Andrew went down to the ocean floor in the solo cage. Soon after he got onto the bottom, she came barrelling in and knocked the cage over!

Jumbo appeared to be determined to attack Andrew and went about it in a determined, methodical and very intimidating manner. Only very experienced divers get to try the solo cage, which is equipped with a main wire to the winch on the boat, a signal rope and an inflatable cylinder to get back to the surface. And Andrew said he was not overly concerned, as he was safe in the cage and knew he could get back to the boat, but… Jumbo’s body language and attitude made her intentions very clear. It was a sobering experience that reinforced his belief in the complete unpredictability of the great white shark.

Where to from here?

Both my recent trips were on the new Rodney Fox vessel—the former Darwin-based pearling “mother ship,” which was completely retrofitted in Fremantle (at considerable expense) to provide the expedition platform Andrew and his business partner Mark Tozer needed to move the business forward.

Underwater, South Australia is an incredibly rich and biodiverse part of our great brown land down-under, but apart from great white sharks, leafy seadragons and giant cuttlefish aggregations, it remains largely a mystery. For example, how many people know about the Great Southern Reef, the massive series of temperate water reefs that extend around Australia’s southern coastline, covering around 71,000 sq km from New South Wales around the southern coastline of Australia to Kalbarri in Western Australia?

I have personally been fortunate to have done a number of trips to different parts of South Australia and believe it offers the most interesting diving in the country. Yet so very little of it is known and explored, so I was particularly intrigued by Andrew and Mark’s plans for the new vessel. I led with, “Do you have the right boat now?” The answer to which was an unequivocal and very firm, “Yes.”

Andrew explained that the boat, formerly called the Elizabeth Bay, was designed and built in Fremantle (at the same shipyard where the recent retrofit was completed) for open-ocean service. This was a really key detail, because any boat that ventures out into the Southern Ocean must be built to deal with the weather and seas that can blow up there.

Both Andrew and Mark are now confident that the rebuilt and renamed Rodney Fox gives them the platform they need to embark on the expeditions they want to do. Top of the list is Pearson Island in the Investigator Group Wilderness Protection Area, some 63km southwest-by-west of Cape Finniss on the western coast of the Eyre Peninsula. The area around Pearson is a marine sanctuary known for its pristine biodiversity.

Then there is the wonderful, but largely explored coastline of Kangaroo Island that Andrew and Mark are looking to circumnavigate as part of a dedicated expedition. A little farther out timewise, but also firmly on the agenda are Tasmania, the far western coast of South Australia, and a trip across the Great Australian Bight to Western Australia. Interesting times ahead! ■

Special thanks to Andrew Fox for his contributions to this article. For more information, visit: rodneyfox.com.au

In more normal times, Don Silcock is based in Bali, Indonesia, but is currently hunkered down in Sydney during the pandemic and enjoying Australian diving. Find extensive location guides, articles and images on some of the best diving locations in the Indo-Pacific region and “big animal” experiences globally, on his website at: indopacificimages.com