We jump into the water as a pair of bull sharks swim past. As we descend into the depths of the Great Blue Hole off the coast of Belize, the light slowly dims. Bubbles from our regulators form silvery plumes that cascade to the surface.

Contributed by

At 60 feet (18m), there is a noticeable thermocline as we descend into cooler water.

When we reach 110 feet (33m), we see giant stalactites hanging from a limestone ledge. Slowly finning, we pass them in what amounts to a topless underwater cave. Because so little sunlight penetrates to this depth, we don’t see much evidence of life. Below us is a purple emptiness.

Jacques Cousteau popularized this dive after he anchored the Calypso here in 1972 and explored the Great Blue Hole. During the Ice Age, the hole was above sea level and part of a complex of underground caves. The roof of the hole collapsed. As the ice melted, the seas rose more than 300 feet (91m) and the cave became a sinkhole 1,000 feet (300m) across and more than 400 feet (122m) deep.

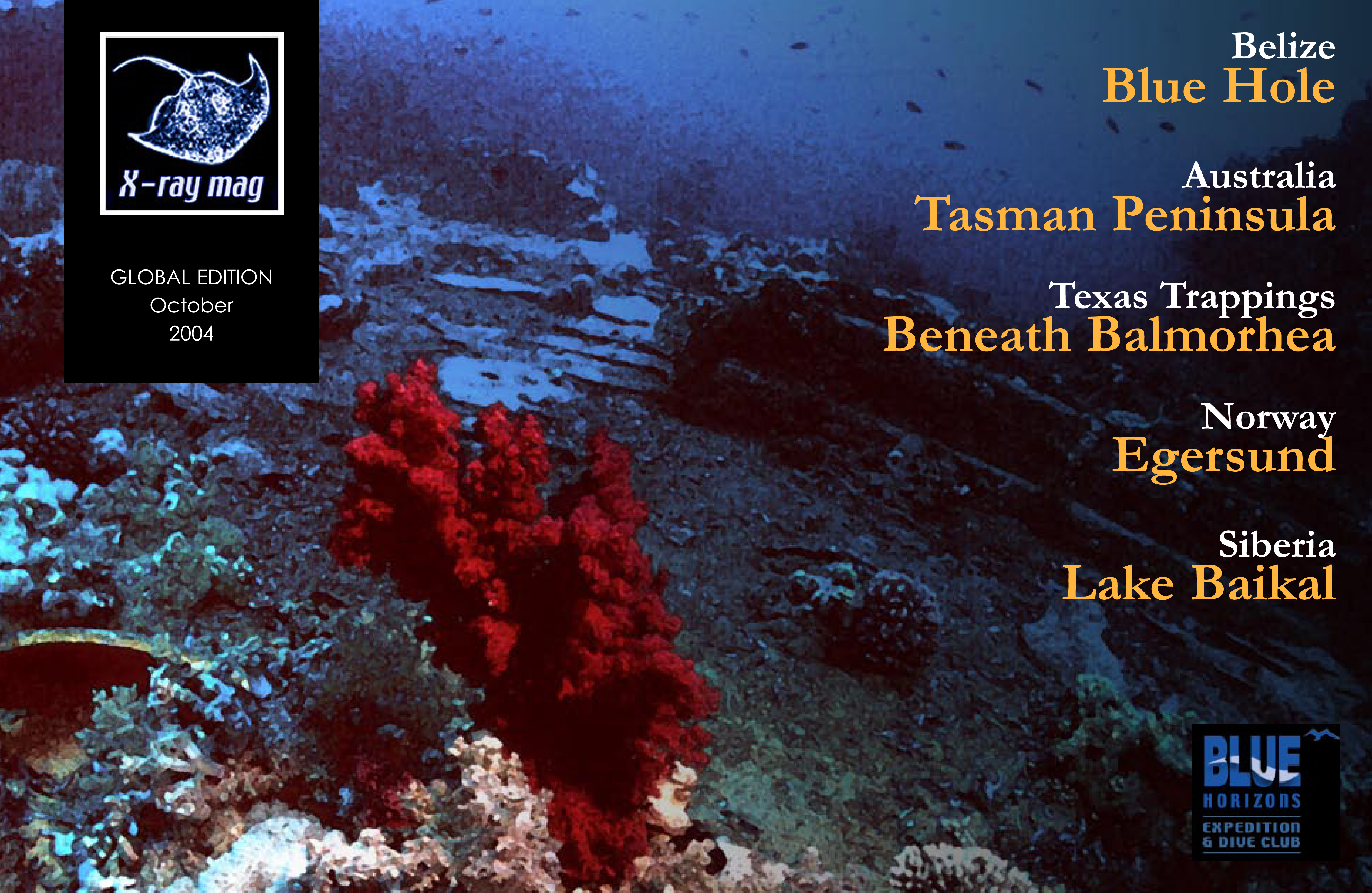

Seen in an aerial photograph, the Great Blue Hole looks like an eye - an unblinking, perfectly round blue iris in the midst of a coral reef. Not surprisingly, the Great Blue Hole has become Belize’s most famous dive site.

Belize, formerly known as British Honduras, is a tiny country wedged between Mexico and Guatemala below the Yucatan Peninsula on the Caribbean side. It is protected by the second-largest barrier reef in the world, after Australia, making it a prime site for divers and snorkelers.

The Great Blue Hole is at Lighthouse Reef, the outermost of Belize’s three coral atolls about 60 miles (96 km) from the mainland. I was diving with Turneffe Flats Lodge, a fly-fishing and diving resort.

Non-divers came along for this adventure. They were able to snorkel the colorful reefs surrounding the Blue Hole and then visit a nature sanctuary.

Before our dive, Juan Vasquez, our dive master, sketched the Blue Hole on a white board and went over the dive plan and cautioned us about the hazards of deep diving.

The Great Blue Hole pushes the limits of sport diving. Divers descend to 130 feet (40m) or more, where the stay is limited to eight minutes to avoid decompression sickness.

Nitrogen narcosis, also called "rapture of the deep,’’ often affects divers who venture below about 120 feet (36m). It’s not unpleasant for many, like the buzz from a three-martini lunch. But "narced’’ divers have been known to die doing foolish things, like taking their regulators out of their mouths and handing them to fish.

Vasquez reminded us that good buoyancy control is essential in diving the Great Blue Hole. At about 60 feet (18m), water pressure causes divers to loose buoyancy. Without adding air to our buoyancy compensators, we could free-fall toward the bottom, over 400 feet (122m) down.

And of course you can always just run out of air. At 130 feet (40m), divers breathe five times as much air as on the surface - and it goes quickly. Vasquez dangled a spare tank and regulator 18 feet (5m) below the dive boat to make sure we would have enough air to make a five-minute safety stop at the end of the dive.

Despite the hazards, virtually all divers dive the Blue Hole safely. It is protected from currents and provides a safe learning environment for deep dives.

On the way back to the surface, we saw a spotted moray eel while the bull sharks circled past. After our safety stop and surfacing, we needed to take a long break to allow the nitrogen in our bodies to dissipate.

Our dive boat took us to Half Moon Caye, which looks like everyone’s vision of a tropical island: white sandy beaches with swaying palm trees and a patch of jungle inhabited by green and spiny-tailed iguanas.

We enjoyed a picnic lunch and a short hike through the jungle to a reserve for the nearly extinct red-footed boobies and more common frigate birds. An iguana gave us a stony gaze from its perch in a tree.

A ladder provided access to a viewing platform at treetop level, where we saw nesting boobies and frigates. It was mating season, and the male frigate birds inflated bright red neck pouches to impress the females.

The frigates wheeled over our heads, came in for awkward landings and panted in the steamy heat as they sat on their nests.

After the break, the snorkelers explored the water from shore while the boat took the scuba divers to a classic wall dive where we saw pristine coral, giant sponges, lobsters, purple sea fans and too many kinds of fish to list.

We cruised through underwater tunnels in the reef as colorful parrotfish filled the water with grinding sounds as they nibbled at the coral.

One of the divers, Rob Greene of Costa Mesa, said he counts the Great Blue Hole and surrounding water as one of the top 10 "must-dive’’ spots in the world. He was blown away by the variety of sea life and the pristine condition of the reefs.

The boat picked up the snorkelers, and we went to our final dive and snorkel spot: "The Aquarium.’’ Here in the shallow water, Vasquez opened a bag of bread underwater and was quickly surrounded by colorful yellow-tailed snappers.

I didn’t pass them my regulator. They seemed to be breathing underwater without any help.

IF YOU GO

There are many scuba diving operations in Belize - based in Belize City or Ambergris Caye - that visit the Blue Hole. Turneffe Flats offers saltwater fly-fishing, scuba diving and marine ecotourism for up to 16 guests at a time. Air-conditioned beachfront cabins, proximity to unspoiled coral reefs, personalized service and small dive groups are part of the charm of this intimate resort set on a tropical atoll. Dive instruction is available on site. Information: (800) 815-1304 or visit www.tflats.com.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #1

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #1

- Log in to post comments