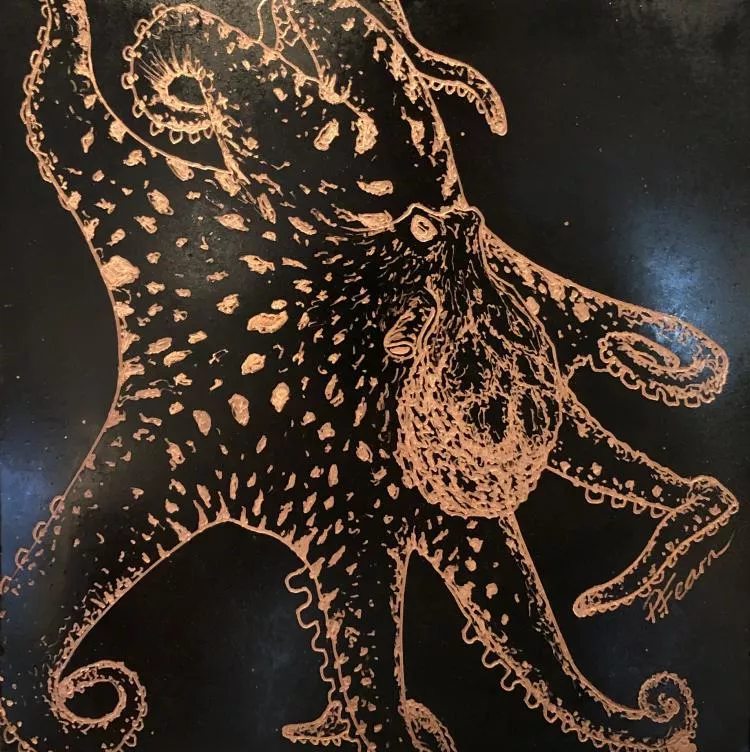

British artist and avid diver Paul Fearn paints beautiful underwater scenes and marine life on copper metal plates, using unique patinas that evoke the ambiance and watery depths of the underwater realm. X-Ray Mag interviewed the artist, who is based in West Sussex, to learn more about his unique artistic process as well as his perspectives on diving and saving the fragile ecosystems of our oceans.

Contributed by

X-RAY MAG: Tell us about yourself, your background and how you became an artist.

PF: As a small child, a relatively difficult start to life ensured that I became somewhat introverted in my early life, so solo activities became favourites. Reading and drawing allowed me to pass hours in my own company, and when I was adopted into a wonderful family in a suburb of South London at the age of five, they encouraged me in these pursuits, buying me books and taking me on regular trips to the local library.

I devoured travel stories like they were chocolates—especially the Adventure series by Willard Price, which are now very outdated and deal with the sticky subject of collecting specimens for zoos. However, they did awaken two things in me, a love of wildlife and a passion for travel.

My family really got my travel bug going with two trips to Greece in my early teens, and from the age of 16, I was travelling solo wherever I could get to and whenever I could afford it. Across Europe, I would spend days walking with my sketchbook getting purposefully lost. By now, my art was coming on leaps and bounds, and whilst I had not yet found a style, I had the patience to really develop my technical drawing.

However, life has a habit of getting in the way, and after spending four years studying languages at university, I ended up in a 12-year career working for the UK Civil Service. It was there that I met my wife who, already an advanced PADI diver, introduced me to scuba diving.

Following austerity measures in 2008 onwards, the opportunity for voluntary redundancy arose and I grabbed it with both hands. That allowed me to pursue my career as an artist, and I spent a good couple of years figuring out what I wanted to do and how I would do it. I began entering major competitions and managed to reach the finals of the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation’s “Wildlife Artist of the Year” award four years in a row. I had also been reaching out to galleries, and shortly after, I landed my first contract with a gallery in the south of England.

X-RAY MAG: Why fish and marine life? How did you come to these themes and how did you develop your style of painting?

PF: My style and subject of artwork really developed hand-in-hand. I began experimenting with patinating sheet copper between 2012 and 2014. At first, I was still a generic wildlife artist, painting and drawing everything from pelicans to elephants. But the process of developing different patina finishes to the copper really started leading me towards marine life, as many copper patinas tend to be shades of blues, greens, verdigris and aquamarines.

In 2007, my amazing wife had bought me a PADI open water course prior to my Egypt trip, and honestly, I did not get on well with it. A day of dive tables and acronyms confused me enough, but the second day of practical skills, with 20 divers and instructors crammed into the deep end of a cloudy swimming pool, ensured that I thought, “This isn’t for me.” However, we arrived in Egypt a month later, and whilst my wife went out on the boat, I did a refresher course in the swimming pool with two very good instructors. The fact I could even see what was around me made an instant difference.

That afternoon, I was out on the boat myself for my first open-water dive—a shallow reef called Shaab Petra, not far from Hurghada. I jumped in, terrified that I would make some sort of mistake, run out of air, get claustrophobia, or worse. As I bobbed around on the surface with my instructor shouting encouragement, I gave the descend signal back to him, deflated my BCD and saw the water line rise above my mask.

I was feeling the panic start to rise as I slowly descended, and then, as if it knew, a little sergeant major damselfish came up to my mask and said hello. It just came up and had a look at me, and as I stared back at it, I realised all other emotions had disappeared; there was just this incredible curiosity about the little fella, and him towards me. I was captivated. It was the same fish I had seen in a million aquariums but this one was in the wild, and I was in his territory. That one tiny fish dispelt all of my fears and changed my life.

So began the slow change from wildlife to marine artist. I found myself returning more and more to the underwater world as my theme, hungry for more and more encounters. Since then, my wife and I have dived hundreds of times across the northern hemisphere, and we have plenty more trips planned. And the more I have dived, the more my artistic style has naturally developed, to the point that I no longer think about the process but more about the subject, and the process just “happens.”

X-RAY MAG: Who or what has inspired you and your artwork and why?

PF: It is very hard to pick out artists or movements that have inspired me, as I tend to take a little of something from everyone and everything, but there are some standouts. In my early career, my technical ability leant heavily on the Dutch still-life painters, and images such as [the 16th-century German artist] Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros.

But as my style has progressed towards the patinated copper sheets, I have found myself drawn more towards the less figurative creative processes of Gerhard Richter, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. But my biggest boost has probably come from a fantastic artist, Herman Lohe, who was, for a while, resident in a studio next door to mine in Kingston Upon Thames.

Herman and I used to chat for hours about art and the processes involved, and he certainly gave me a few pointers in the right direction. It was he who taught me, as an adult, that the paintings I thought were finished were not necessarily so, and who reinstilled in me the patience in the process that I had had as a child.

X-RAY MAG: What is your artistic method or creative process?

PF: The process of creating my artworks differs from piece to piece, but most follow the same basic rules. First is the cleaning and de-greasing of the copper. Then, it is sanded down with increasingly fine sandpaper to give the patina a textured surface to “bite” onto. I then usually paint out the coral reefs, koi, or any areas I want to remain “clean” with a resist [acidic solution].

Once that is complete, I choose which chemicals and additives I need in order to achieve a specific colour and texture. I have many recipes that I keep fairly secret, but the one I started with (and the most widely used) is the verdigris patina, which is made from a simple 50 percent fine salt and 50 percent malt vinegar recipe. The solution is then either poured or sprayed onto the copper sheet, which is put into a fume chamber to “cook.” This gives it a similar finish to the Statue of Liberty [in New York City], I just speed up the process, which would naturally take years, to a few hours or days.

Different chemicals give different colours and finishes; for example, sprinkling sea salt on top of a patina solution can result in a much more textured finish. I personally like that, as it starts to mimic the different visibility conditions in the ocean.

There has been a lot of experimentation over the past ten years with different solutions. Some acids have eaten the copper away completely and some have sat in a fume chamber for days without making a mark on the surface of the copper. In addition, many patinas, which I thought were winners, simply washed away during the next part of the process where I have to spray the patina with water to stop the reaction from continuing.

My years of experimentation have left me with a raft of solutions and cooking times that I can use to achieve a myriad of results. I think, looking back on this process, I took to the patination element well as historically I have not liked painting “backgrounds.” In this way, I can use a natural process to convey a natural substance like seawater.

Once the patinated copper has been washed, dried and lacquered, the next part of the process can begin. This is where the actual paints come out.

I use acrylic paints for the colours that I cannot achieve naturally, and they also help to “pop” out from the background. First, the corals are painted in a pseudo-realistic manner, with squiggly lines making up underwater city structures. And then, the fish. Neon-coloured fish in front of multi-coloured corals surrounded by a blue salty sea? Yes, please!

And this is where patience again kicks in, as some of my larger pieces can contain thousands of fish. Just as if one were painting a flock of birds, not all of the fish are painted in high detail, but enough have to be, in order to backfill the empty water with faraway anthias that can be represented with a deft flick of paint. I am attempting to represent the vast shoals here that are often seen hovering above the corals.

X-RAY MAG: What is your relationship to the underwater world and coral reefs? How have your experiences underwater influenced your art? In your relationship with reefs and the sea, where have you had your favourite experiences?

PF: My wife and I each have hundreds of dives to our names—we do not know how many, as we stopped keeping log books years ago. But we are very definitely what I would term “lazy divers.” We have certainly been on drift dives with ridiculously strong currents, we have explored the cenotes in Mexico, kitted up at the roadside and clambered over rocks in Malta to get to the sea, and also run out of air underwater, but our perfect dives have been less than 20m deep, where we are relatively near to the surface. The colours there are more pristine, there are more anthias and shoals, and we can spend a longer time underwater—which is especially good for filming, as I only take a GoPro with me to capture footage.

It is this “close-to-surface” world that I really want to portray in my art, as I want to give the viewer an idea of what it is like to be underwater. If you are trying to tempt somebody to become a diver, chances are you will more likely achieve that by taking them to a place that looks like an aquarium than a place with sharks and deep-sea critters. Don’t get me wrong, I love sharks and diving with them, but I am aware that this is not what your average human wants to think about when they go snorkelling.

Of all our diving adventures together, I would pick out two dives as favourites. The first was a whale shark encounter in the Maldives, which was simply stunning—enough said. The second was at Eagle Point, Bagalangit, in the Philippines. The Mabini headland juts out from the mainland, and Marikaban Island, just opposite, creates a highway for pelagic species. On the one dive, we saw ocean-going tuna and pygmy seahorses. It was also on that dive that I unknowingly stopped at a very busy cleaning station.

When my wife looked around for me, she said she saw a human-shaped ball of fish. She finned back to join me, and the two of us were enveloped in a neon shoal tickling away at any bare skin they could find (quite a lot, as we were wearing shorties). Every time we giggled and released bubbles, they would all move away, then instantly come back to carry on cleaning. It was honestly a magical experience, and we both felt that we had been “accepted” as water-dwelling creatures.

X-RAY MAG: What are your thoughts on ocean conservation and coral reef management and how does your artwork relate to these issues?

PF: It is insanely easy to ignore the underwater world when you do not live in it. Even for us divers who regularly go six months between dives (or years when Covid-19 struck), the importance of actively helping oceanic life to thrive can be lessened by events in our daily lives above water. That is why it is vitally important to do what we can, when we can.

The small and obvious ways of helping are numerous. For example, during our dives, we always carry a bag to collect any litter we find in the sea, and a flat-tipped knife to free anything caught. To date, I have not had to free anything from fishing lines or plastic, but it is better to have it and not need it than the other way around.

Many of the ways to help save the ocean lead to things we should be doing in our daily lives anyway—e.g., using less water and saving energy where possible. I have in the past year been taking cold showers (with a blast of hot water at the end); it cuts down on the time I spend in the shower and heating the water. It is also part of a larger plan to get used to cold-water immersion, so that I can dive more sites closer to home in the United Kingdom, cutting down on air travel and making the trips more affordable.

With my artwork, I want to give people another insight into these underwater worlds, so that even non-divers may start to care about those environments. The more intriguing I can make the artwork, the more people can be converted to become part of the worldwide army of humans trying to make a difference.

X-RAY MAG: How do you choose species to paint? Do you work from specimens or take underwater photographs of these species, and if so, what camera gear do you use?

PF: As previously mentioned, the only thing I take with me on my dives is a GoPro, which I turn on to film as soon as anything interesting happens underwater. I find it helps me to use video, which I can freeze-frame later, as generally, I point the GoPro in whichever direction I am looking, so I get a much more natural view, which more often than not, includes the surrounding coralscape. This helps me plan out my entire artwork, rather than painstakingly setting up a perfect photo of an individual creature. I have seen many a photographer miss a passing shark, turtle or eagle ray whilst taking five minutes to photograph another shrimp.

In general, the singular specimens do not form the subject of my art, rather it is the environment and the feeling of being immersed in it that I am trying to capture. It is only at the very end that I will think, ok, I need more anthias here or a Napoleon wrasse there; I think I have some footage of one somewhere… It is the environment that is the star and not the one fish.

X-RAY MAG: What is the message or experience you want viewers of your artwork to have or understand?

PF: The biggest message that I would hope to get across is that diving opens up another part of our world that, whilst needing to be respected at all times, can be welcoming and transformative. If I can get landlubbers to jump into the sea on their first dive due to discussing the ocean world with me, then I am just as happy as when achieving a sale.

X-RAY MAG: What are the challenges or benefits of being an artist in the world today? Any thoughts or advice for aspiring artists in ocean arts?

PF: The art world, just like everything else, has suffered in the last couple of years due to the cost of living, and the Covid-19 pandemic, in particular. As an artist, you have to be ready for these times, so my strongest advice would be to have a backup plan, a part-time job or a continuation of your previous job, to keep the bills paid. Then, and this is the bad news, you will have to try to fit in a full week of art into the evenings and weekends.

Having a full portfolio and an online presence is vital if you are approaching galleries, but also try entering competitions first to make sure your art is well-received and/or sellable. You ideally want to have 10 to 20 fully finished pieces ready for any gallery you approach.

Lastly, if you are painting the underwater world, you really have to know it. It will show, if you don’t. Nobody can get away with using online imagery that is not theirs. Online reference is fine for working out the anatomy of different species, for example, but you have to know which fish sits next to which. You would not paint a seahorse next to an orca, for example; it just would not feel right, even to non-divers. Know how species interact with each other, such as anthias and lionfish (run away!) or cleaner wrasse and giant moray eels (time for your dentist appointment, sir!).

X-RAY MAG: How do people—adults and children—respond to your works?

PF: In most of my larger pieces, I tend to hide a Nemo-looking clownfish amongst the hundreds or thousands of others, which keeps the children entertained for at least a few minutes. But the main responses to my art are either a fascination over the process, or twenty questions about diving: “Is the underwater world really that beautiful?”, “Where have you dived?”, “Where would you recommend for a first-time diver?”, etc.

I, like nearly all other divers, love talking about diving, so it often happens that a sale comes about naturally through the conversations I love having anyway. And if no sale occurs, well, I would have still generated an interest in diving in somebody new.

X-RAY MAG: What are your upcoming projects, art courses or events?

PF: All artists need to develop their work over time—no matter how far along on their artistic journey they are. I am now looking at using engraving more as a finishing layer to my pieces, emphasising the swirls, eddies, currents and thermoclines we encounter under the sea. I also want to explore using some more realistic painting techniques to complement the somewhat abstract and chaotic nature of my patinated backgrounds. But more than anything, I have a desire to keep exploring the world’s oceans and to venture farther into the southern seas, experiencing more environments that I can portray in my future pieces.

X-RAY MAG: Is there anything else you would like to tell our readers about yourself and your artwork?

PF: Lastly, I would just like to say a big thank you to everyone who has stopped to look at, talk about or purchase my artwork, whether they have spoken to me in person or looked at my art online, at an exhibition or in a magazine. I never realised when I began my diving journey just how welcoming, fun and friendly the dive community was. It is so easy to get talking to people, whether you are part of a couple or single, and we have made more friends over the past 16 years than we can count.