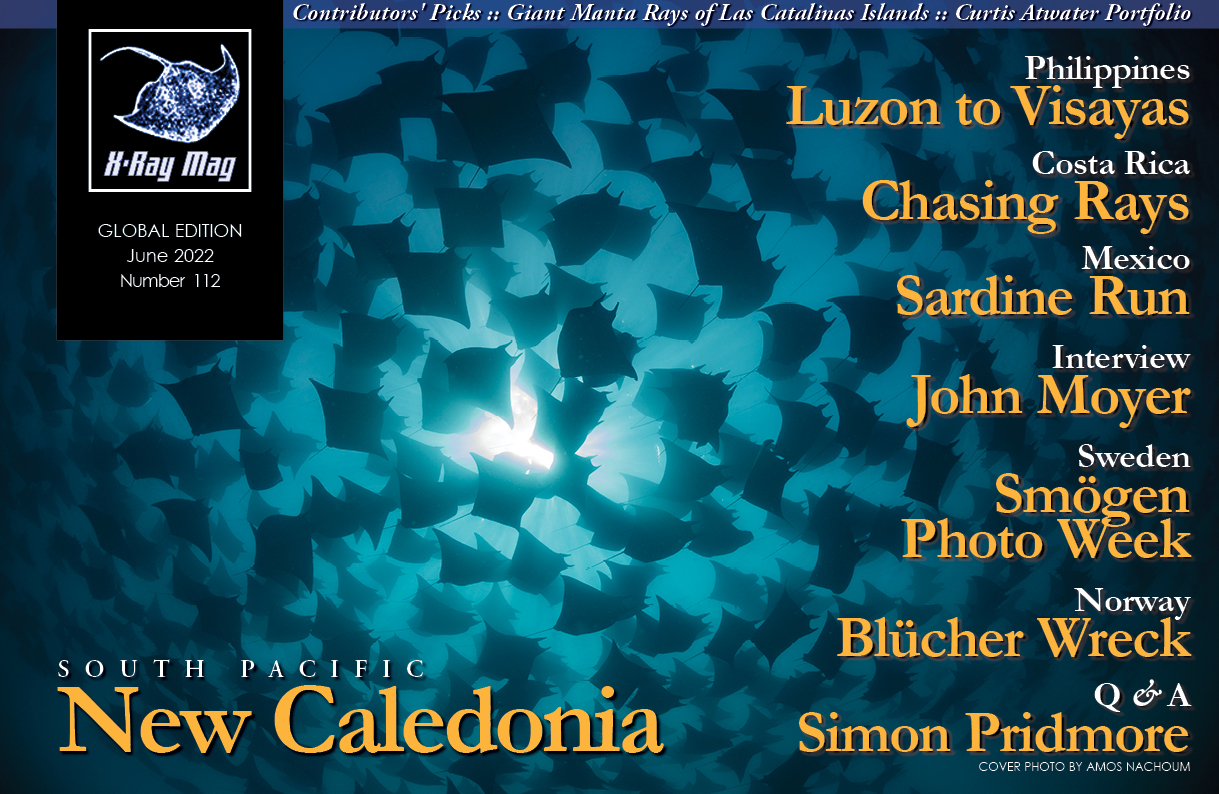

Considered the longest continuous and second largest in the world, the reef systems of New Caledonia have some of the most diverse concentrations of reef structures on the planet, providing a home for a vast diversity of species, including 2,328 fish species. It is an important site for nesting green sea turtles, and there are also large populations of dugongs and humpback whales. Pierre Constant shares his adventure.

Contributed by

It really started as one hell of a trip. I had originally booked a return flight to Wallis and Futuna—west of Fiji and Tonga—in the central-western Pacific, which would transit through Nouméa in French Caledonia. Unfortunately, it seemed I had to make an official request to the COV (Commission des Vols) for a special permit, provide documents and then wait a month to get a confirmation—which I received precisely one week before I left France.

In addition, it was also compulsory for me to spend a week in total confinement in Nouméa, before I would be allowed to fly to Wallis. It was no use to have been already vaccinated against Covid-19, with the compulsory booster shot, plus the negative PCR test less than 72 hours before departure. Nope! One still had to spend a week in isolation, take an antigen test two days after arrival and again seven days after the completion of the “confinement.”

To make a long story short, I was denied access to Wallis and had to change my trip itinerary to cover only New Caledonia.

The week of confinement was boring, a total loss of time and a substantial loss of money too (1,000 Euros). By the time I left New Caledonia one month later, the compulsory quarantine was lifted to “boost tourism,” as they said. To say I was fuming would be an understatement. Welcome to a South Pacific “paradise”!

Geography

Situated 1,980km north of New Zealand, 1,470km east of Australia, 630km south of Vanuatu and 1,350km west of Fiji, New Caledonia lies in the southern hemisphere at 21°25’ South and 165°30’ East. Part of Melanesia in the western Pacific, this bone-shaped island is 400km long (250 miles) by 40km wide (25 miles), with a total land surface of 18,576sq km.

Known as “Grande Terre,” the main island’s highest summit is Mt Panié, rising up to 1,628m in the northwest. Four main islands are found to the northeast and southeast: Ouvéa, Lifou, Maré (these three islands make up the Loyalty Islands), and the Isle of Pines, as well as numerous smaller islets and myriads of coral reefs.

Located on the Indo-Australian Plate, New Caledonia is part of the mostly submerged continent of Zealandia. Orientated northwest to southeast, this landmass is a fragment of the ancient continent of Gondwana, which broke off from Australia about 66 million years ago and drifted in a northeasterly direction, to reach its present position 50 million years ago.

Driven by alternate plate collisions and rifting, the rock formations range from 290 million years (Permian) to the present. These include igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks. The Loyalty Islands ridge is seen as a volcanic island arc.

The subduction of the Australian Plate along the South Loyalty Basin was blocked by New Caledonia, resulting in “obduction” (when a continental plate goes under an oceanic plate, and not the other way around) during the Eocene and Oligocene.

Still a complex phenomenon to geologists, this nevertheless explains the occurrence of the Peridotite Nappe (part of the metallic rich Earth mantle) at Grande Terre. It is the alteration of the peridotite rocks that transform into laterite. As a consequence, we have the nickel-rich content of the dark red soil, mined today in various parts of Grande Terre.

A central mountain range divides the mainland along its length, with the highest peaks of Mt Panié in the northwest and Mt Humboldt (1,618m) in the southeast. Exposed to the southeast trade winds, the eastern coast has lush green vegetation. The western coast is drier, with large savannahs and plains for farming.

Blessed with a tropical climate, the hot humid season extends from November to March. Temperatures average 27 to 30°C. Between December and April, tropical depressions and cyclones pound the island with strong winds from 100 to 250km/hour and heavy rainfall. The cool dry season extends from June to August, with average temperatures in the 20 to 23°C range.

History

Early traces of human presence date back to the Lapita culture (1600B.C. to 500B.C.), when highly skilled navigators and agriculturists sailed from Southeast Asia, and across the Pacific, over a period of 2,000 years. Primitive settlements were concentrated along the coast (1100B.C. to 200B.C.).

The first European to sight New Caledonia was British explorer James Cook on 4 September 1774 on his second voyage. He gave his name to the famous Cook’s pine (Araucaria columnaris) found everywhere on the coral islands. French navigator Louis Antoine de Lapérouse sailed by Grande Terre in 1788. The Loyalty Islands were visited by whalers between 1793 to 1796.

A dark past

Later on, visiting ships were primarily interested in sandalwood. This resource would slowly be replaced by “blackbirding” from French and Australian traders, when Melanesian and Pacific islanders (from New Caledonia and Loyalty Islands) were lured into slavery and forced into hard labour in sugarcane plantations in Fiji and Queensland. In the early 20th century, children from the Loyalty Islands were kidnapped to work on the plantations and mines of Grande Terre.

French counter admiral Auguste Febvrier Despointes officially took possession of New Caledonia on 24 September 1853, in the name of Napoleon III. Grande Terre became a penal colony in 1864, and 22,000 criminals and political prisoners were sentenced to hard labour in New Caledonia. The same year, nickel was discovered and mined 12 years later.

Excluded from the economy and mining work, the indigenous Kanak people sparked a bloody insurrection in 1878, led by Chief Ataï of La Foa. A guerilla war resumed after many of the central tribes united together to fight the invaders, resulting in many deaths on both sides. Chief Ataï was killed.

A second revolt and guerilla war erupted in 1917. This slowly brought on the creation of the independentist movement (FNLKS) of Jean Marie Tjibaou (once a priest) who would be assassinated in May 1989, by a Kanak from Ouvea.

This event and what followed triggered the deep resentment evident today against the French presence. This is despite three referendums confirming the attachment to France, which met an overwhelming Kanak abstention.

Arrival in Hienghène

It was a 390km or a five-hour drive from Nouméa, to reach Hienghène on the northeastern coast. The main highway, beyond La Tontouta International Airport, followed the southwestern coast to Kone. I was amidst the green hilly countryside, with the central mountain range on the right. A sinuous road crossed the main divide, as it gained in elevation among pine trees, bamboo groves and exotic giant tree ferns. Here was a reminder of New Zealand’s rainforest landscapes.

One hour later, the eastern coast was in sight, and the forever twisting road ran along the coast beyond Touho. A small sleepy village, Hienghène was the core of the independentist movement, considering the number of FNLKS flags hanging in front of every house and property. This was a genuine tribal area where custom rules are the norm, so one is expected to behave accordingly!

Babou Dive Centre sat in a quiet location of the countryside. Founder Thierry Baboulène’s assistant, Florent, had no knowledge of my arrival. “There will be no diving until the weekend, because of the weather and the dirty sea conditions,” he advised, adding that it had been raining recently. The visibility was affected by the discharge of nearby rivers, with the swell and waves on top. This meant I had three days to kill in front of me.

Land-based explorations

At the base of the black dolomite Linderalik cliffs, I found a chalet at the nearby Gite Kunwe Foinbanon. A stroll took me to the viewpoint of La Poule Couveuse. A dark, sharply eroded black limestone islet jutting out of the lagoon, mimicking a nesting hen, it is the touristic symbol of Hienghène.

The following morning saw me climbing the trail, overgrown with high grasses, to Col de Ga Wivaek (Wivaek Pass), where there was a stunning panoramic viewpoint overlooking the Linderalik cliffs and back lagoon, La Poule Couveuse, and the mouth of the Hienghène River. A sweaty two-hour round trip.

After a fifteen-minute drive north of town, the road led to the Bac de la Ouaième, an old ferry barge on a metallic cable that transported vehicles back and forth across the river. This remarkable piece of history is the only one left on the island. Farther away was the breathtaking multitiered Colnett Waterfall, a chance for another hike and a lovely dip in freshwater pools.

Set on tribal lands, the cliffs of Linderalik were enticing because of the existence of a cave tunnel that cut through the limestone, presently closed, unfortunately.

Unintentional trespass

Passing by in search of it, I discovered with awe the sepulture of an ancient human, with bones and skull next to a conch shell, attribute of a minor chief. To my stupor, I was to find out later that the place was taboo—a former hideout of cannibals who, in the past, would lure their victims there.

If one had been seen there, one would have gotten into serious trouble with the local owners. I realised then that New Caledonia was no different from Papua New Guinea and the Melanesian Islands, where permission is needed to enter or trespass any land.

Finally, the diving starts

A Frenchman in his fifties, Thierry, the founder of Babou Dive Centre, had settled in Hienghène in 2000. Powered by a 300HP Suzuki outboard, the centre’s aluminium boat was rather full today, with eight divers on board.

Cathédrale. We sailed 12 miles out across New Caledonia’s lagoon, one of the largest in the world with a surface area of 24,000 sq km. It was a 45-minute trip to the outer barrier reef. The dive site was Cathédrale. We submerged into a gully, under some arches and swim-throughs, with gorgonians. Thierry pointed out a pretty purple flatworm with an orange line along the back. Among the fish life, I noticed one-spot snapper (Lutjanus monostigma), eye-stripe surgeonfish (Acanthurus dussumieri), Napoleon wrasses (both male and female), a wahoo, a black saddle coral grouper (Plectropomus laevis), two bluefin jacks and a grey reef shark.

Pointe aux Cachalots. The successive dive at Pointe aux Cachalots was a maze of gullies, swim-throughs and small tunnels in the reef structure, where openings in the ceiling created an amazing display of sunbeams and light. There was not much fish life here, besides a wandering grey reef shark. The water temperature was 27.5°C.

The next day was a repeat of the dives done earlier, with better visibility and more photo opportunities. Among others, there were the paddletail snapper (Lutjanus gibbus), a green jobfish (Aprion virescens) and an exhilarating school of smallspotted dart (Trachinotus baillonii) under the surface. A big silvery pompano with a scissortail showed up as well. On our way to the dive site, a joyful school of spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) gave us a welcome spinning show.

Poindimie

One hour southeast of Hienghène was the town of Poindimie, where I had planned a week of diving. Sadly, things did not go as expected. On the first dive, I went with a lady instructor and a few divers. She spotted an attractive nudibranch at once, and so I changed the wide-angle lens to the macro lens.

By the time I set back the wide-angle lens on the housing again, the dive group had disappeared into the labyrinth of canyons and tunnels. I had no clue where to go. Instead of calling off the dive, I decided to swim around the block and shoot photos on my own. Fortunately, I caught up with the group before the end of the dive.

Koumac

My next port of call was Koumac on the northwestern coast, where I had heard of a dive shop. No answer was made to my email, and when I got there, the place was closed. No one answered the phone either. Someone mentioned that the dive centre had ceased operations.

Natural heritage

Being isolated for such a long time, after the separation from Gondwana, the flora and fauna of New Caledonia have evolved on their own for millions of years. Out of 3,400 species of plants, 74 percent are endemic—that is, 2,530 species. It is not only endemic species, but also entire genera and families.

Out of the 44 species of gymnosperms, 43 are endemic. Out of the 35 species of Araucaria in the world, 13 species are endemic to New Caledonia, including the renowned Cook’s pine. Many species of tree ferns are endemic, like the giant tree fern (Sphaeropteris novaecaledoniae), over 10 metres tall, found in the Parc des Grandes Fougères (Giant Fern Park).

In regard to the 183 species of birds found here, 24 species are endemic, including a friarbird, a lorikeet, a parakeet, a cuckoo shrike, two honeyeaters, a myzomela, a white eye, the goliath imperial pigeon and the red-throated parrotfinch, among others.

The most emblematic of all is the flightless, bluish-grey, 55 to 60cm tall kagu, which walks in the humid forest of the lowlands, in search of worms, insects and small reptiles.

I was unable to spot it at first at Sentier des Cagous, but in the Parc Provincial de la Rivière Bleue (Blue River Provincial Park), I fell upon a couple by chance, one early morning, as they suddenly appeared in front of me, hissing like a snake to warn me of their presence! Distinctively charming and unique.

Eleven species of fish are found in rivers and lakes. A living fossil related to ammonites, the nautilus is found in waters around New Caledonia. Last but not least, an extinct species of giant horned turtle with an armoured tail (Meiolania platyceps) from the mid-Eocene was discovered here. A full skeleton was also found in a sand dune on Lord Howe Island, farther south.

Isle of Pines

My last week in New Caledonia was reserved for Isle of Pines, a celebrated island paradise and tourist hotspot, a half-an-hour flight southeast of Nouméa. Based in Ouameo Bay on the northwest of the island, Kunie Scuba Centre was the place to go.

Although I was hoping for a week of diving, I got only four days in the water. The weather was decent, but the visibility was not optimal. The year 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the Kunie Dive Centre, the oldest dive operation in New Caledonia.

Friendly reception

Spotting a salt-and-pepper beard and a ponytail, Pierre Emmanuel Faivre was an outgoing 38-year-old from the Jura mountains of eastern France. He took over the dive centre in 2015 with his Japanese wife. He welcomed me heartily with a super-friendly, laid-back attitude.

I was then introduced to his team of Kanak instructors, Narcisse and Nico—both great guys—as well as to tough, serious-looking Antoine, the stocky, muscular captain. A very wide and comfortable dive boat with matted benches, the Naiad is a white semi-rigid inflatable boat from New Zealand, with two powerful 250HP Suzuki outboards.

The diving was done at the coral islands of the Gadji tribe, which had given Kunie Dive Centre exclusive access to the area ages ago. La coutume (custom) had to be respected at all times.

Crested with abundant vegetation and Cook’s pines, the low-lying uplifted coral islands had their shores carved out by wave action. These dotted the turquoise blue lagoon like a collection of mushrooms, some even with arches. This was indeed an exotic landscape of the South Pacific.

The water temperature averaged 26.8°C, but it did drop down to 25°C at times, forcing me to don a 3mm wetsuit, as I was literally shivering underwater! I realised afterwards that there was a conspicuous upwelling in the southeast of New Caledonia.

Passe de Gié. Diving Passe de Gié yielded a school of black snappers, rainbow runners, clown sweetlips, a whitetip shark resting on sand and the usual sight of pink skunk anemonefish (Amphiprion perideraion) and Clark’s anemonefish (Amphiprion clarkii).

Kugié. The nearby dive site of Kugié was a haven for zebra sharks (Stegostoma fasciatum). I was fortunate to approach up to three of these awesome creatures. (Always approach them from the front, as to not scare them). They were dozing off serenely on the white sandy floor.

A giant bell-shaped mangrove whipray (Himantura granulata) took off from under a veil of sand. The dotted sweetlips (Plectorhinchus picus) and the foursaddle grouper (Epinephelus spilotoceps) were also present, as were many specimens of elephant trunkfish sea cucumber (Holothuria fuscopunctata).

Ilot Gié was a place for schools of yellowband goatfish (Mulloidichthys vanicolensis) and gold-spot breams (Gnathodentex aureolineatus), peacock flounder (Bothus mancus) and—flying like a magic carpet over sand—the blue-spotted stingray.

The most amazing encounter, however, was that of the New Guinea wrasse (Anampses neoguinaicus), endemic to the southern Great Barrier Reef, New Caledonia and Lord Howe Island.

Jardin d’Eden, on the outer slope of the barrier reef, had much cooler water, close to 25°C. Cruising grey reef sharks were common, and there were orangutan crabs (Oncinopus sp.) on some bubble coral.

An unusual sight was that of the Japanese boarfish (Evistias acutirostris), a large fish striped black and yellow, with a protruding trumpet nose and yellow fins. “There is only one left, as the other two have been wiped out by the last cyclone,” lamented Pierre. It was also common on Lord Howe Island.

Final day of diving

Mur aux Pouattes. Pierre offered a special treat on the last day: a dive at Mur aux Pouattes, at the oceanic side of the barrier reef. “My favourite site!” he beamed. Indeed, this was where the big action was—not to mention pelagics too.

We encountered red snappers (Lutjanus bohar), schools of surgeonfish, a school of yellowtail barracudas (Sphyraena flavicauda), an inquisitive great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda), streaming grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos), a farandole of bigeye jacks (Caranx sexfasciatus) and a surprising silvertip shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus).

“You may even see silky sharks in the right season,” Pierre added. To complete the experience, he showed me three egg cowries (Ovula ovum) on Sarcophyton soft corals.

The highlight of the dive turned out to be the sight of three specimens of a species never seen before: painted anthias (Pseudanthias pictilis) sporting three colours—lavender with a red caudal peduncle and a red tail with a white band on it. Psychedelic for sure!

Les Grottes de Gadji. Upon conclusion, Pierre led me to one of his favourite spots: Les Grottes de Gadji (Caves of Gadji). This was a labyrinth of tunnels, arches, swim-throughs and tight passages, where openings in the roof created laser sunbeams and attractive light shows.

Torch in hand, he moved like a fish bathed in bliss. Plenty of pronghorn spiny lobsters (Panulirus penicillatus) dwelled in the darkness as well as many striped hinge-beak shrimps (Cinetorhynchus striatus), red and white banded.

Despite the poor visibility, the experience was entertaining. “You should come in November or December, pure blue water and great viz,” he disclosed. Thanks to Narcisse and Nico, I was truly satisfied with my experience and by the positive spirit of Kunie Scuba Centre.

One regret though… I missed out on diving the Loyalty Islands—and Lifou in particular—due to lack of time and the complicated schedule of the Betico ferry. Chances are, I shall have to come back one day!

SOURCE: Wikipedia.com

Thanks go to Babou Côté Océan at Tribu de Koulnoué, Hienghène (babou-plongee.com), and Kunie Scuba Centre at Ile des Pins (kuniedive.com)