Photographing in ambient light can be a choice or a necessity. It is therefore important to develop an adequate sensitivity to ambient light in order to be able to judge whether it is the best option for shooting a particular scene. Claudio Ziraldo offers some insights and tips on how to improve your underwater images.

Contributed by

On a dive in the Philippines, I was descending along the outer wall of Pescador Island, a pinnacle that rises from the seabed to about six metres above the surface. I looked up and saw the silhouette of a dive boat crew member clinging to one of the outriggers of our “bangka” (traditional boat), silhouetted against the blue sea.

Instinctively, I switched on my hand-held strobe, which I held out to the opposite side, and shot a couple of frames. The sound of a steel rod tapping against an air tank was my dive guide’s signal that I had fallen behind and needed to catch up with the other divers in our group.

At Menjangen Island in Bali, Indonesia, I had the opportunity to dive along the wall of the dive site POS 2, which had one of the most spectacular colonies of gorgonian sea fans of all types and colours that I had ever seen. After exploring different views, I had fallen behind again. The rest of the group had already rounded the point where the dive boat was waiting for us, but I wanted to photograph two small overlapping gorgonians that were in pristine condition and fully backlit.

Looking through my camera, I saw that the dive guide, who had been waiting for me underwater, had re-entered the frame. He was not in an ideal position, but I photographed the scene anyway, using a fisheye lens and two strobes.

I then signalled for him to move behind the gorgonian. I switched off the strobes and shot the scene again. And here is the result: two pictures of the same subject, one in which the colour aspects of the image have been emphasised; and the other, with ambient light, in which the graphic aspects of the image have been enhanced instead.

Shooting in current

There are situations where it is difficult to decide whether to use a strobe or not, or where a strobe should not be used at all. In the case of currents, a strobe would illuminate the infinite number of suspended particles stirred up by the movement of the water, ruining the image irreparably.

In this situation, not only is it essential to avoid getting caught in the current and risking injury, but also to use a fast shutter speed to “stop” the action, freezing the movement of the elements in the shot. I would advise you not to go below 1/250th of a second.

In southern Egypt, I managed to snorkel close to a pod of striped dolphins. There was a bit of a “swell,” and the surface was rippled by the movement of the waves.

I decided from the start not to use a flash, because there was so much light under the surface and also because of the time of day. Moreover, using a speedlight flash would have eliminated the interesting patterns created by the water’s reflections of light on the dolphins’ bodies.

Again, by using a quick shutter speed to “freeze” the movement of the water on the surface, I was able to capture a special “ice” effect and, of course, avoid the problem of “blurring” in the group of dolphins.

In the cave at the Umm Khararim dive site in the southern Red Sea, I only used the strobe when there was an element in the foreground with a strong colour component (alcyonarians or fish, for example). Otherwise, I chose to keep the strobes off and, where possible, find an element of interest (diver with torch) to give vitality to the photo.

In these situations, an accurate balancing of the light is very important—more specifically, try to create a sort of “frame” effect, where the much brighter exterior “absorbs” the underexposed areas, while retaining its characteristics. The sun’s rays, coming down from above, complete the picture. To get this kind of image, it is important to work in the middle of the day when the ambient light is at its peak.

Over-under shots

For over-under shots, a strobe may or may not be used, depending on the situation. It is indispensable when there is a large degree of difference between the light on the surface and the light underwater, such as when taking backlit shots at sunset.

In this particular case, however, the photo was taken without using the speedlight flash. It was exposed for the external light in order to avoid overexposure. The underwater area is slightly darker than it was in reality, but still discernible, and the photo appears balanced.

Wrecks

When photographing underwater wrecks, there are situations where the use of a speedlight flash is necessary and others where it is better to work with ambient light. This was the case when photographing the Khanka wreck at Zabargad Island in the southern Red Sea.

In this scene, I inserted two lights (torches). The first torch is held by a diver in the foreground, to make the image more dynamic, and the second torch is held by a diver in the background, to emphasise the sharp perspective and give a sense of scale to the whole scene. Coordinating two collaborators is not easy, but when the team works, the results are rewarding.

Backscatter

Here, I present two shots where the presence of large amounts of nutrients in the water made the use of flash virtually impossible.

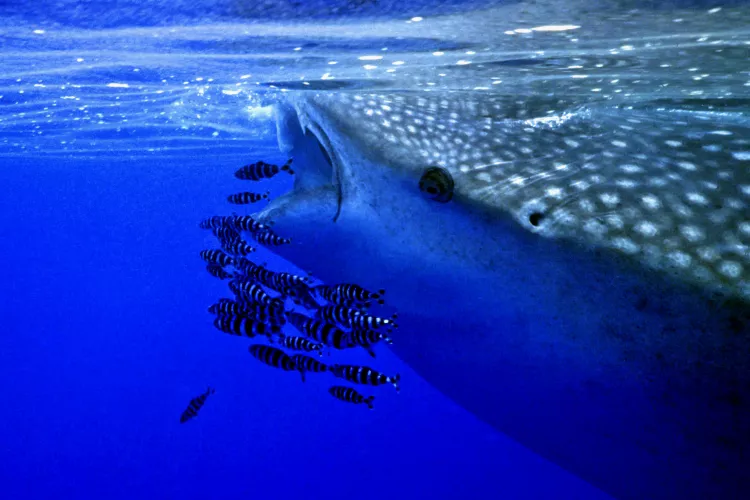

The photo of the manta ray was taken at Mesharifa Bay in Sudan. These beautiful animals congregate here in October because the water temperature and the presence of particular surface currents cause large quantities of plankton to concentrate in the area.

The manta ray is reflected by the surface of the water, while the light passing through the rippled surface creates strange patterns on its wing. A similar effect can be seen in the picture of the whale shark, which was taken in the Red Sea, north of Hurghada, where I had the opportunity to capture a very special moment.

To sum up

The situations in which it is appropriate and/or necessary to photograph with ambient light are many and varied. In this article, I have mentioned just a few of them, and the subject is far from exhausted. ■