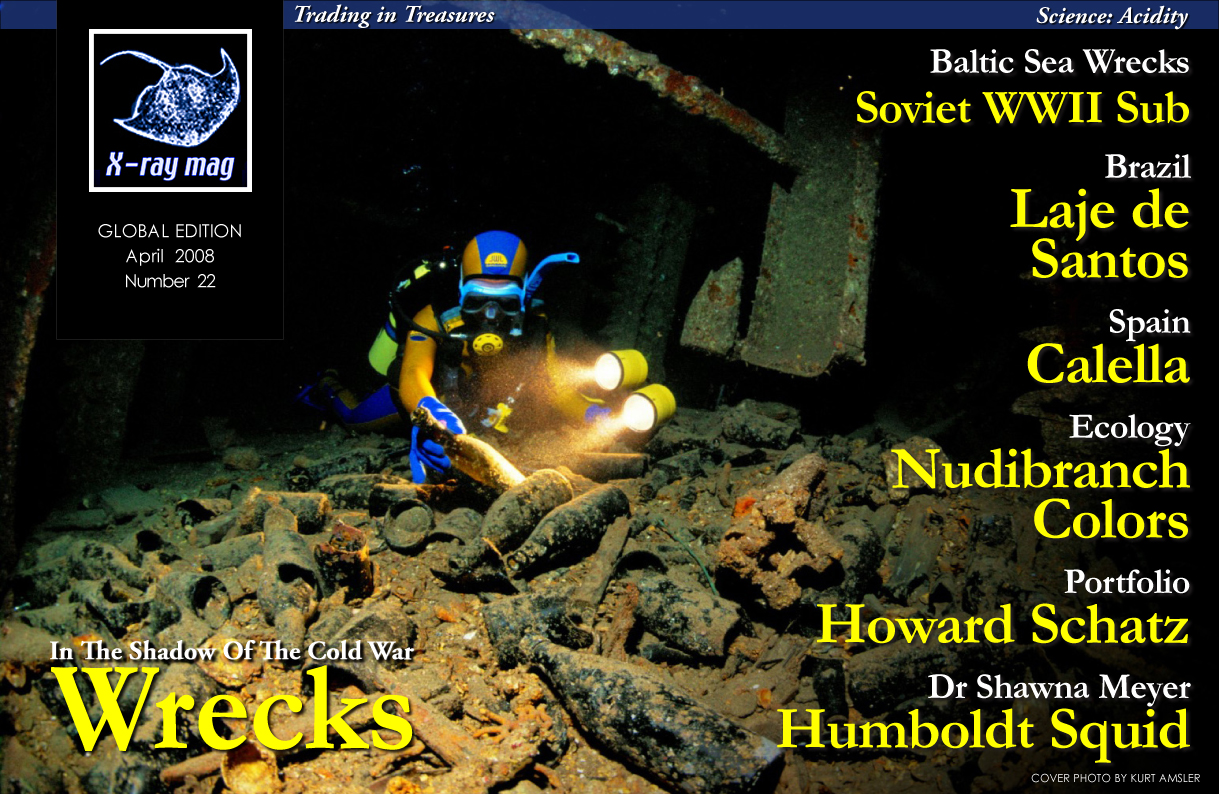

Do you plan to explore a deep virgin wreck? Is it your dream to discover a unique cave system deep in the jungle? Have you heard about a Blue Hole miles off shore and want to give it a try? In any case, chances are you’ll be diving in a remote location where emergency medical systems are not much more frequent and up-to-date than traffic lights in the Himalayas.

Contributed by

Factfile

References

Provision of first aid. Diving Medical Advisory Committee (DMAC) - DMAC11– download at www.dmac-diving.org

Medical equipment to be held at the site of an offshore diving operation – DMAC15 – download at www.dmac-diving.org

Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. American Heart Association in collaboration with International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Download at http://www.erc.edu/

The four R’s of managing a DCI injury. Bill Clendenen, DAN Training coordinator. Divers Alert Network – download at www.diversalertnetwork.org

Acute management of decompression accidents in normal and remote locations, by Dr Alessandro Marroni, DAN Europe

Guideline for the treatment of diving accidents, a summary. European Journal of Underwater and Hyperbaric Medicine, Volume 4 No. 2, June 2003

Guidelines needed for management of remote DCI. Chris Wachholz, DAN Duke University medical center

How to deal with an unconscious rebreather diver. Cedric Verdier. Download at www.cedricverdier.com

Keeping up with the time: applications of technical diving practices for in-water recompression. Richard Pyle, Bishop museum, Hawaii

Hazardous marine life. Bill Clendenen and Dan Orr, DAN. Download at www.diversalertnetwork.org

Training as a Diver Medic Technician (DMT): Many training centers all over the world, the most famous ones being in Australia, DDRC in the U.K., Dick Rutckowsky in the U.S.

What constitutes an emergency and what kind of emergency may I face?

What do I need to bring in order to reasonably deal with possible emergencies?

In other words: How remote is remote, and is it necessary to have a physician present 24/7?

If you travel a lot, chances are you will come to discover that, unfortunately, quite a few medical facilities around the world will bear a resemblance to a hangar during a bombing campaign, with medical staff being overworked and people running around as if the news of Armageddon coming just broke. So, a first reaction would be to think about how to become self-sufficient should an accident occur. However, in the real world this is rarely possible. So, we have to find a compromise, and proper planning is a good place to start.

Emergency planning includes several steps...

Risk assessment

Any technical diver has been exposed to “What if” scenarios. For a remote exploration, the best option is to lock down all the team in a small room with only filthy sandwiches to eat until they come out with a comprehensive list of all imaginable problems that could happen during the exploration, underwater as well as at the surface.

You then have to review this list and remove what you can’t really deal with anyway such as tropical hurricanes, tribal riots, terrorist attacks, outbreaks of Ebola, and so forth. Realistic problems range from cuts and wounds to decompression illness. They can be caused by:

- The equipment we use. (Engine, propeller, ropes, etc.)

- The dive we plan to do (dive profile, number of dives per day, number of days diving, etc.)

- The environment where we dive (off shore reef or wreck, overhead environment, etc.)

- The location of the expedition (tropical climate, local food, etc.)

Available resources

Wherever you dive, even in the most remote locations, there are always some resources you didn’t think about. As is often the case with technical diving, it all comes down to using what is available and to be creative about it.

In case of an accident, you need:

People to handle the emergency.

The best guy for the job is you. The fact that you actually plan for any potential accident makes you the perfect choice. But the whole team should be involved. A simulated emergency training exercise could be run prior to the expedition, or even better on the first day of the expedition.

Consider taking training courses to better deal with an accident. The obvious choice is a technical rescue course, but this is not commonplace. You can sign up for a CPR/first aid course, O2 provider course or even better, a DMT course (Diver Medic Technician, see references at the end of this article).

Prepare and practice some procedures (rescue, evacuation, etc.) and make sure everyone knows them. And think about what local medical staff, Navy and search and rescue teams could be called in to help even recreational divers.

Specific equipment.

The first things people think about are the first aid kit and the oxygen kit. A complete first aid kit is probably the most essential piece of equipment to bring along to a remote location, as the most common accidents are not diving-related, but rather related to the location or equipment such as cuts, wounds, burns, food poisoning, etc. In regards to administering oxygen, deco tanks can often replace dedicated oxygen kits, as long as they have an appropriate regulator for both conscious and unconscious patients. Closed-circuit rebreathers can also be used when nothing else is available.

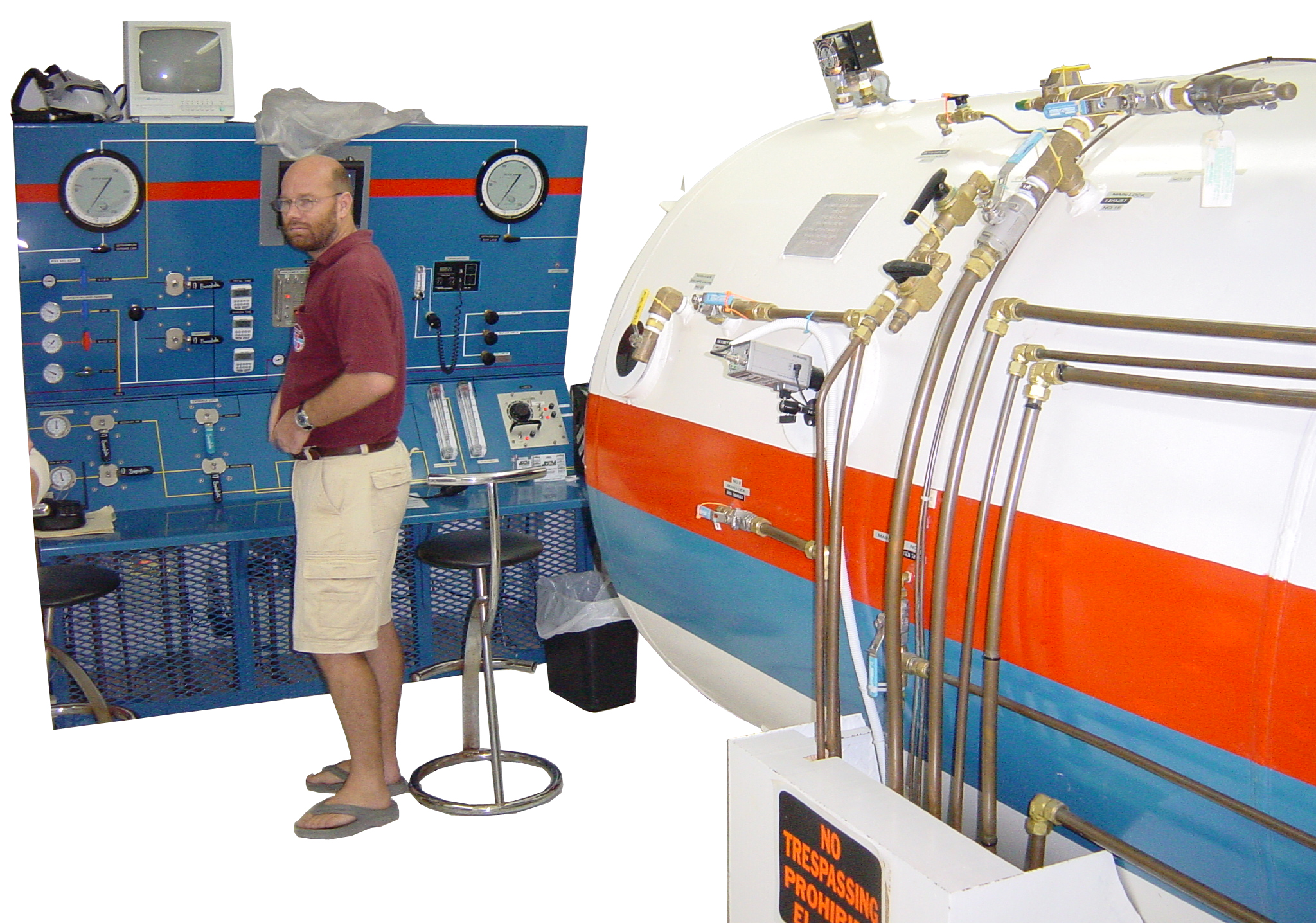

Technical divers who don’t have two left hands with ten thumbs can easily build other equipment such as stretchers, deco stations or habitats out of garbage and junkyard stuff. Except for the most gifted ones, recompression chambers are seldom part of an expedition, and the team will mostly have to rely on local facilities. A pre-dive visit is always a good idea in order to inform the medical staff and to organize the most efficient evacuation and treatment.

Evaluating additional needs

As we said, even people with just basic first aid skills can efficiently handle most of the accidents a diving team would encounter. However, most divers will not be capable of treating more severe injuries, except those who have been trained by Harry Potter.

The best choice is obviously to have a hyperbaric physician participating in the expedition, either as a diver or as a member of the surface support team. A physician will come in quite handy when it comes to on-site treatment of an injury or a diving-related condition. If your expedition is so remote and the dive profiles really over-the-edge, it might become necessary to consider a portable recompression chamber. It’s obviously the tool of choice if a decompression Illness occurs, and you are so far away from the nearest recompression chamber that you need to hire a space shuttle to make it there in time.

But a portable chamber (even a foldable one) is big and a logistic nightmare to transport. It is also quite an investment, so renting one might be the most, or only, affordable option. Some models can be easily folded and do not need a huge amount of gas to be operated. However, even the best chamber is of no use unless you have people capable of operating it. And don’t forget that these kinds of chambers are mainly for evacuation purposes, so you obviously need to arrange for adequate transportation, too.

You might also need some communication tools as well. Calling for help in remote locations sometimes means the only options are using satellite phones, long range radio transmitters, or emergency radio beacons (EPIRB). Technology develops fast, and options that were extremely pricey only a few years back, could now be affordable.

Setting up emergency procedures

All sorts of problems can happen when you’re in a remote location. However, many small injuries can easily be treated on-site. No need to call in a medivac helicopter and team of paramedics for a small cut or a hangover.

Therefore, only four main emergency procedures should really be considered:

► A missing diver. In this difficult situation, the first step is usually to determine if a diver or a team of divers are lost at the surface or underwater. Being lost at the surface often means a long wait and an extensive search pattern in a rough sea (as if this ever happens in calm seas and perfect weather!). Being lost underwater often means facing strong current and no SMB deployed, or worse, having to rescue an unconscious diver. The actual emergency procedures and the related training depend, to a large extent, upon the location. Being lost in a cave deep in the jungle, or drifting on the surface at sea by night, are completely different scenarios.

► An unconscious diver. There’s no magic here! Rescuing an unconscious diver underwater has nothing to do with pure luck or imagination. Some of the techniques are simply too complex to be invented on the spot while under a high level of stress. Only properly trained divers can do a proper rescue. Read some of the articles cited in the reference list and practice, practice, practice.

► A decompression illness. Tools are of paramount importance when divers get bent. But oxygen, fluids and drugs are just tools. Some divers in very remote locations might also consider In-Water Recompression procedures (IWR), if such things do exist. IWR is obviously not the best way to treat a diver, but it has probably saved some lives in the past. Some remote expeditions include the techniques and the related tools such as Full-Face mask, Deco seat, etc., in their emergency procedures. Some IWR protocols are cited in reference at the end of this article.

► An urgent evacuation. There’s not much good in attempting a surgical operation while equipped with only a spoon and a Swiss army knife when your training is made up of watching “Survivor” on TV. When you’re dealing with severe injuries, DCI or life-threatening conditions, you must have planned a fast evacuation procedure beforehand. You can’t improvise a fast transportation and a smooth evacuation when every minute counts.

■