You just have to do it to understand it. Until you have experienced it, the name itself does not stir the emotions as much as the other types of diving. Once you have experienced the treasure hunt for yourself, you will be hooked. Marketing specialists would agree that it is probably misnamed and they have even tried to rename it, but nothing has stuck the same way as the coined term “muck diving.”

Contributed by

Factfile

Brandi Mueller is a PADI IDC Staff Instructor and boat captain living in the Marshall Islands.

When she’s not teaching scuba or driving boats, she’s most happy traveling and being underwater with a camera.

For more information, visit: Brandiunderwater.com.

References:

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/mantis_shrimp

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/nudibranch

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ophichthidae

http://www.theseahorsetrust.org/seahorse-facts.aspx

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/ribbon_eel

http://www.molluscs.at/cephalopoda/index.html?/cephalopoda/sepia

So, what is muck diving? The term can be used to describe several types of diving but usually involves diving in areas you wouldn’t initially think about diving in. Under piers and bridges, right off shore in the shallows, such as seagrass beds; sometimes below shipyards, where you might only expect to find garbage and often poor visibility... but always with amazing critters. These spots that may not look like the best diving locations have turned out to be some of the best places to find and photograph the weird and the wonderful of the ocean.

Where to muck dive

Some of the world’s most popular muck diving locations are in the Coral Triangle, the region between the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. This region has the highest biodiversity in the ocean, and favorite muck diving places include Indonesia’s Lembeh Strait, many parts of the Philippines, and the shallow waters right off Papua New Guinea.

Muck diving occurs in other places as well, with one of the most popular muck diving sites in the United States being under the Blue Heron Bridge in Florida. Divers spend hours in shallow waters finding seahorses, nudibranchs, octopus, batfish, crabs, shrimp, eels and more. Other locations around the world include places in the Caribbean, Canada and Australia.

What will you see?

The list is far too long to be completely covered in one article—in fact, several large books won’t even cover them all—but here is a list of some of the favorites and why the critters of the muck are so darn cool.

Mantis shrimp. Often found peering up at you from a burrow in the sand or from a crevasse in coral, mantis shrimps are some of the coolest critters in the sea. You won’t want to mess with them though, as some species have the ability to “smash” or “spear” with a second pair of thoracic appendages; there is enough force in that punch to generate tiny bubbles, which cause a shock wave that can stun or kill prey on its own. They have even been known to crack camera ports, so don’t get too close.

Beyond being phenomenal fighters, mantis shrimp have eyes with 12 to 16 types of color-receptive cones (humans only have three). They have compound eyes that allow them to see from three parts of each eye, giving them depth perception that likely helps them out in their ability to attack prey with such speed and accuracy. The eyes of the mantis shrimp are perched on stalks that allow them to move independently of each other.

Some can be beautifully colored too, such as the peacock mantis shrimp, which is probably one of the most colorful critters of the muck. With purple and blue eyes, and bodies of green, red and blue, they are always exciting to see and photograph. Mantis shrimp are thought to mate monogamously for their entire lives, and the duty of taking care of the eggs (which are pink in the peacock mantis shrimp) by holding them in their arms, can fall on both males and females sharing the task in some species.

Seahorses. Seahorses are another favorite ocean animal no matter where you dive. They are commonly found in the muck, coming in many shapes, colors and sizes. Beautiful with their unique half-horse and half-fish profile, we can’t help but love them.

Some of the smallest seahorses are the pygmy seashores, which are about 2cm tall or slightly smaller than your pinky fingernail. The largest is the Pacific seahorse, which can be up to 30cm tall.

Another reason we love seahorses: Pairs often mate for life and their reproduction habits are quite interesting. When two seahorses are about to mate, there is an elaborate courtship dance between the two of them, with lots of twisting of their tails together. Eventually, the female deposits her eggs into the male’s pouch, which then fertilizes them and essentially becomes pregnant (big belly and all!). In the world of seahorses, it is the males give birth, to many tiny seahorses.

Pipefish. Cousins to the seahorse are the pipefish. Looking like a stretched-out seahorse, both share several similarities. For one, some pipefish species also have the males brood the offspring. Pipefish also come in many colors and sizes, with one of the smallest being the pygmy pipe dragon, which even up close looks like nothing more than a stray strand of algae. They are usually 2-3cm long and thread-like skinny.

Some pipefish are colorful, like the banded pipefish, which has pretty red stripes, and others are uniquely shaped, such as the ghost pipefish. Many blend in with their surroundings perfectly, such as the ornate pipefish, which swim among crinoids looking just like them—or the robust ghost pipefish, which can alter their colors so as to vanish into a seagrass or seaweed habitat.

Scorpionfish. Masters of disguise, scorpionfish have the ability to blend in with their surroundings, but sometimes their hiding spots are given away in the muck; at other times, they hide even better in the black sand or silt common to muck dives. Almost all are venomous. Many species of scorpionfish exist with some of our muck favorites, including the lionfish, leaf scorpionfish, rhinopias, waspfish, stargazers and more.

With a face only a mother could love, the scorpionfish may get a bad rap because it will leave a severe sting if you do not see it and accidentally rub up against it. But photographers love them, and it is always amazing to see only rocks and coral, and a second later, you realize it is actually a scorpionfish.

Octopus. Another favorite for critter finders and photographers alike are the many shapes, sizes and colors of octopus in the muck. One of the most popular (and the most deadly) is the blue-ringed octopus. It is also one of the smallest, being only 12 to 20cm. Brilliant blue rings identify this octopus, although it can make them fade away, showing only a white or cream-colored body to blend in with its surroundings. Usually, when it is agitated, it shows the vibrant blue.

Mimic octopus and wonderpus are two other amazing octopi. Both have long and skinny tentacles with brown and white stripes. Mimics are thought to mimic other animals and will mold their bodies into different shapes to look like a flounder, lionfish, eel or another reef species.

The smallest species are the tiny pygmy and algae octopi, which can be as small as 4.5cm. Larger species include the coconut octopus, named thus because it likes to make its home in objects such as sunken coconut shells, discarded bottles and other trash. All octopus species have three hearts; and their blood is green instead of red because it contains a copper-containing protein called hemocyanin, instead of hemoglobin.

Cuttlefish. Cuttlefish belong to the class Cephalopoda, like the octopus, and they have eight arms and two tentacles. The smallest of the cuttlefish is the pygmy cuttlefish, which can be 15cm long, while the largest can be up to 50cm and weigh over 10kg. Often seeming to interact with divers, they are always a great find during dives.

Cuttlefish communicate by changing their body coloration, and they do this through the use of chromataphores, which contain pigment granules. They also have iridophores, which produce iridescent colors that may look metallic. They are able to change colors and patterns rapidly, either to camouflage themselves or make themselves bright and well-seen—which may be a way of showing aggression, openness to courtship, or other communication with their bright and fast moving colors.

One of the smaller and favorite cuttlefish species is the flamboyant cuttlefish, which can show brilliant red, purple and yellow hues. The flamboyants have 42 to 75 different skin coloration elements (other cuttlefish may have up to 34 elements). It often looks as if it is walking along the sand. When hunting, the flamboyant and other cuttlefish species have two feeding tentacles with suckers at the end that are used to grab prey and bring it to the beak where they are “paralyzed by venom.”

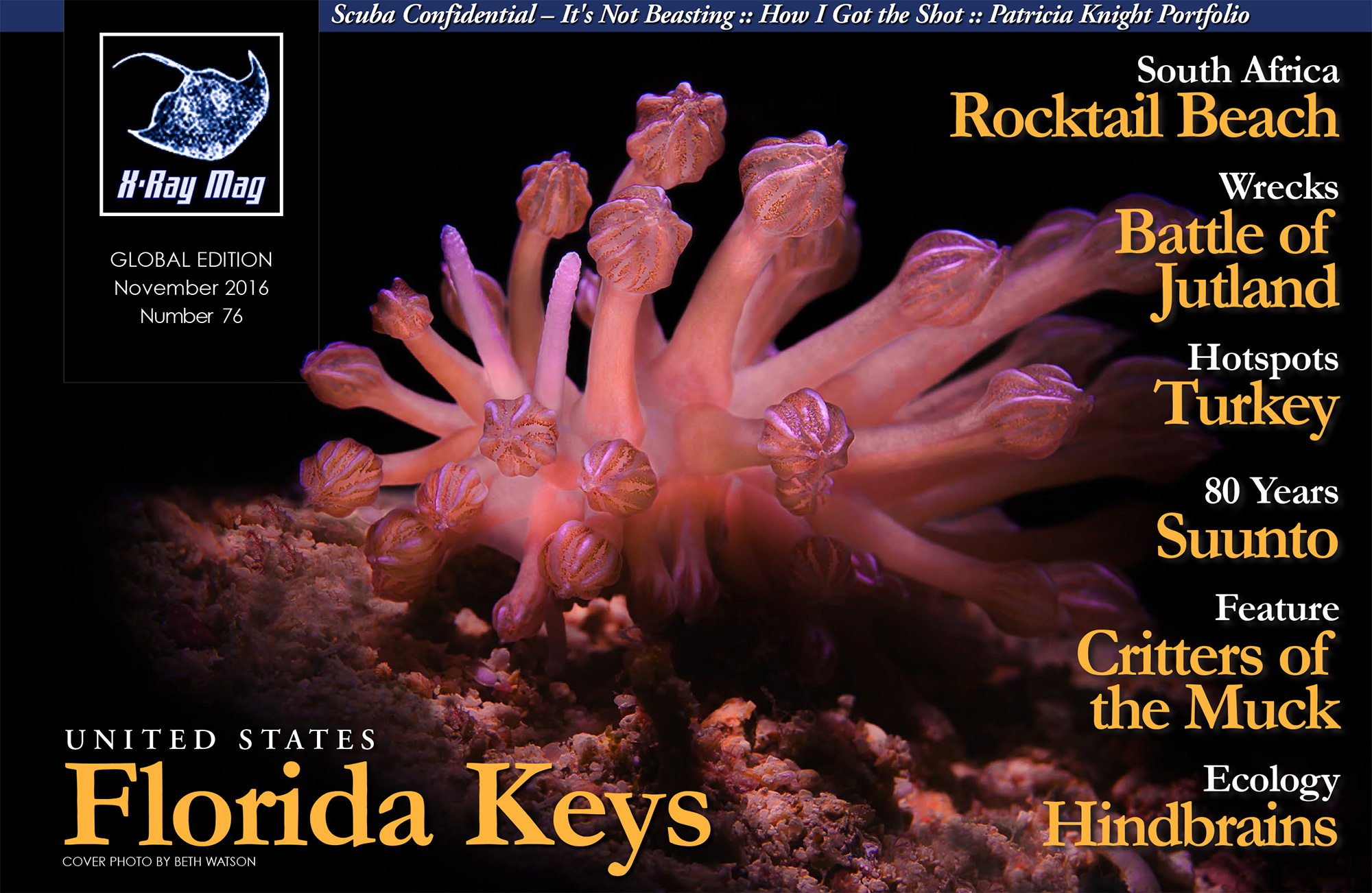

Nudibranchs. When talking about muck diving, one cannot not discuss nudibranchs. Even though they are found worldwide, many species can also be seen in muck diving locations. Nudibranchs are colorful sea slugs belonging to the mollusk family, although they are a shell-less version. Over 2,000 species are known, with more and more species being discovered. Looking like long, skinny, painted Easter eggs, nudibranchs have two rhinophores that project from their heads like rabbit ears, which are used for smelling. They have a tail-like plume of feathers, which is an open gill system through which they breathe.

With so many different species, many nudibranchs have some very exciting habits. Some are cannibalistic and will eat other nudibranchs of different species as well as their own kind. Some species are solar-powered, because they eat algae and hold onto the chlorophyll cells in extensions of their body, which then absorb sunlight and make energy for the nudibranch. Their bright colors also serve as a warning for predators, because many species are toxic from feeding on hydroids and keeping their nematocyst cells within.

Despite being so colorful, finding nudibranchs can be a challenge. They are small and blend in with their surroundings, often being in similar colors to the sponges they eat. So, local dive guides are the key to finding the best nudibranchs in a specific area.

Eels. Eels are a common find on most dives, but eels in the muck tend to be cooler than most. In some areas, there are blue ribbon eels. (The name is misleading because they are not always blue.) This eel actually changes gender and color throughout its life. As juvenile males, they are black, with a tiny yellow stripe on their dorsal. Eventually, they will turn into females and become blue, with a yellow stripe on the dorsal. Then, as they complete sexual maturity as a female, they turn completely yellow for the last phase of their life.

Snake eels are another unique eel that generally strike me as quite creepy. Often seen on night dives, they stick only the end of their heads out of the sand, with the rest of their bodies buried below (sometimes several feet of their bodies are hidden). Blending into their surroundings, they do not move until an unsuspecting fish crosses right over their mouth. Then, like a bolt of lightning, they shoot out and grab the fish, sometimes pulling it back down into the sand or using their long tails to capture the prey. Snake eels can be red or cream-colored, black, or spotted like the Napoleon snake eel. Another popular nighttime snake eel is the stargazer.

And so much more… The above animals are just a few of the many unique and wonderful critters of the muck. There are hundreds of species of crabs and shrimps, colorful gobies and wrasse as well. Juvenile fish of many species also hang out in muck areas for protection until they get larger. Frogfish of all colors and sizes can be found here too.

In addition, there are the Bobbit worms, a terrifying monster of a worm, which hides completely in the sand except for two antennae that feel for a fish to swim over it. When a unsuspecting fish is just above the Bobbit worm, it emerges and uses scissor-like appendages to cut the prey in half, or grab it and drag it completely back into the sand.

Even after years of muck diving, there are still critters on my wishlist I have yet to see, and new things to discover, with dive guides often showing me things of which I have never heard. The treasure hunt is indeed endless.

Tips for muck diving

Get a good dive guide. If you are new to muck diving, the first thing to do is find a good dive guide to help point out the critters. It is amazing how, on your first few muck dives, you may swim right over all the good stuff, and your dive guide will then point to a tiny thing that looks like a piece of dust, and it will become a tiny baby frogfish right before your eyes. Local dive guides also know where certain animals hang out, so your chances of finding them will be better.

Practice good buoyancy. Good buoyancy is a must on all dives, and this is especially true on muck dives as they are often in shallow, sandy and/or silty areas. One misplaced kick can create a sandstorm that will reduce visibility and can cause backscatter in your own and your buddy’s photos. I also highly recommend a pointer stick, not to poke at or harass the marine life with, but to use to stabilize yourself in the sand or on rocks without life, while searching or photographing the muck critters.

Go slow. Going slow is key to finding stuff, as so much of it is tiny. A small patch of sand might look like just sand until you get close and slowly look over the whole area. There may be baby frogfish, nudibranchs or even tiny octopus, blending in with the sand.

Don’t skip the night dives. I know, I know. I am as guilty as anyone of having a lovely glass of wine at dinner after that warm shower and skipping out on the night dive. Like all night dives, muck dives at night are completely different than those during the day. A whole new set of critters come out, and you won’t want to miss them. Behaviors also change at night. Things like hunting can be observed, and some critters, which stay hidden during the day, come out in full force at night.

So, the next time you hear the term “muck diving”, don’t cringe at the thought. Instead, think of all the wild and wonderful tiny stuff in the ocean you will find, turning your dive into a little bit of a treasure hunt. ■