Sliding into brackish water riddled by a seasonal downpour might not be everybody’s idea of a week-end in the Wild West...but for the frustrated winter diver that I am, there is sometimes nothing like the peaty waters of Connemara.

Contributed by

Connemara loughs are like proverbial watering holes: there is no shortage of them. Water is not exactly a rare commodity around here, above and below, out of the heavens it comes in every colour, salted, fresh, not so fresh or with a seasonal Guinness tint. In late summer, a plankton bloom and peat water conspire to create visibility averaging chowder-like conditions, at best. To cap it all, clouds of jellyfish pulsating by don’t help improve the visibility. What a contrast with the clear waters of the Atlantic nearby!

Fed with seawater and fresh water from nearby rivers, sea loughs can bring together an odd mixture of life resulting from the interchange with the sea. A slight current is noticeable with the tide and water clarity can improve. It is a great spot for watching passing shoals feeding by. Shoals of garfish and rainbow trout are not uncommon.

Depending on their relation to the sea, some loughs seem deprived of any visible life, others are just teeming with it. With sea loughs, a layer of brackish fresh water sits over the layer of salt water. In the summer, as the sun filters through the surface, the water takes on an eerie post nuclear glow. The surface halocline acts like a filter and blocks off daylight, soaking up whatever sunshine dares find its way over Connemara.

Mysterious Shallows

Moving along the shallows reveals a sandy bottom of broken shells and gravels. Not the typical mud plain. Beyond the shallows brings you into deeper waters, and in some areas the slope falls sharply into 20+metres. With limited visibility, many dwellers are camouflage experts and blend in with their environment, it takes a while to adjust and spot them. A lot of these mud hoppers are more curious than their sea counterparts, they will come out to gawk at the tourists, stare and hop out of reach.

In places, tubeworms have congregated in huge numbers and developed into full-grown reefs. Clumps of red, orange, yellow and white serpula (tube worms) are fanning themselves in a gentle current. This is the closest I’ve seen to a live underwater Christmas tree. Sitting on a hard base of white tubes, they really stand out against the muddy lough bed. At feeding time, with the reefs in full bloom, the bottom suddenly comes alive.

These reefs are very much alive and support a variety of animals. The colonies of tubeworms act as a magnet for several species and diversity is the order of the day. Sleepy edible crabs are found nestled among clumps of tubeworms. Starfish and brittle star sit atop or in the centre of the reefs when they’re not crawling their way across clumps of colourful umbrellas.

Further along, the reefs are covered with strings of sea squirts in the shape of light bulbs. In places, various weeds and sponges appear to smother the colonies of serpulids, each species competing for space. It seems that the tubeworm colonies have been themselves colonised.

Fish

Fish are not lacking either. Blennies and dragonets are hopping along the muddy bottom, rock cook and wrasse hover around feeding. Blennies are not used to divers and faced with fewer predators than in the sea. In any case, they show real curiosity, attracted by the whirr of the autofocus - a few oblige by posing. May coincides with nest building for wrasses and the reefs are a busy hive of activity where wrasse can be seen carrying along with seaweed twigs. Further along, the reefs have eyes. Scallops are glued to the reefs.

Some are attached to glowing pieces of orange sponge or wedged in a crack. Smaller scallops and mussels are buried in many places. They can be hard to spot and it’s only after getting close that you’ll make out their tiny eyes. Another striking residents are nudibranchs sliming their way across the reefs.

Further along, three lobsters have found a home at the base of a large clump of tubeworms. One of them pops out of its den wielding a pair of claws like garden shears. But they’re not all the stay-at-home variety.

We turn around to face an even bigger specimen trampling the muck. Amazingly, the wily old beast keeps a steady course. I have to make way as he retreats into a hole hindered by two oversized claws. Eat your heart out Popeye! If the size of these animals is an indication of the nutrients available, then the grub here is five-star.

Macro life

In June, nudibranchs and sea hares enlaced in amorous embrace have colonised the reefs. They are obviously thriving in this environment. It is difficult to imagine all these animals surviving on the muddy lough bed. The reefs provide a habitat for these species that would probably not be found here otherwise. Watching these animals will test your buoyancy and breathing control. Serpulids are extremely sensitive to any light, noise or vibrations. The slightest disturbance and the colorful beasts retreat in a wink. Unlike critters that dart away and never reappear, the serpulid worms are soon out again. They cannot leave the reefs, they are the reefs, and I must have aged taking photographs of them.

Deeper, the atmosphere can be downright spooky. Light penetration is minimal and on cloudier days, almost non-existent. Past 20 m, we might as well be diving in a tunnel. A halogen torch cuts through the first meters of water shrouded by plankton and particles. Looking up, the surface is a faint glow. On a sunny afternoon, we hit 25 m of complete darkness in the centre of the lough. I had never been on a night dive in the middle of the afternoon before. Definitely one for the logbook.

In contrast with the colourful reefs seen only a few minutes earlier, the bottom is a plain of mud. The lightest fin kick raises a cloud of soot-like dust. The kind of particles that stay in mid-water and take all summer to come down.

Back to the shallows, sun rays passing through the surface weeds create ghostly silhouettes. After persistent rain, water droplets float on the surface trapped in an oily film. Runoff from the land give the surface a milky appearance. Within the last five meters, the separation line between the layers of sea and freshwater becomes visible.

A horizon line runs below the surface. Looking up from 10 metres, the surface seems to have doubled up into two layers. Crossing the layers is like going through an optical illusion. I wonder if I haven’t gone cross-eyed. A bit like looking through a magnifying glass that won’t focus...After heavy rain, the halocline can be seen up to 5 metres deep.

Dive Center

The nearest dive centre to Clidfen is Scuba Dive West on the Renvyle Peninsula in County Galway. It is a family-run PADI five star dive centre established for many years. It is located on the banks of Ireland’s only fjord, Killary. It is an ideal base to dive and discover the islands of Clare, Inisboffin, Inisturk, and the many wonders of Connemara.

www.scubadivewest.com

Jerome Hingrat is a professional underwater photojournalist from Brittany. His photographs and articles have appeared in a wide range of publications, including SportDiver (UK), Océans (France), Subsea (Ireland) among many others. His work focuses on destinations and subjects ranging from the Amazon to the Indo-pacific to underwater Ireland. www.jeromehingrat.com ■

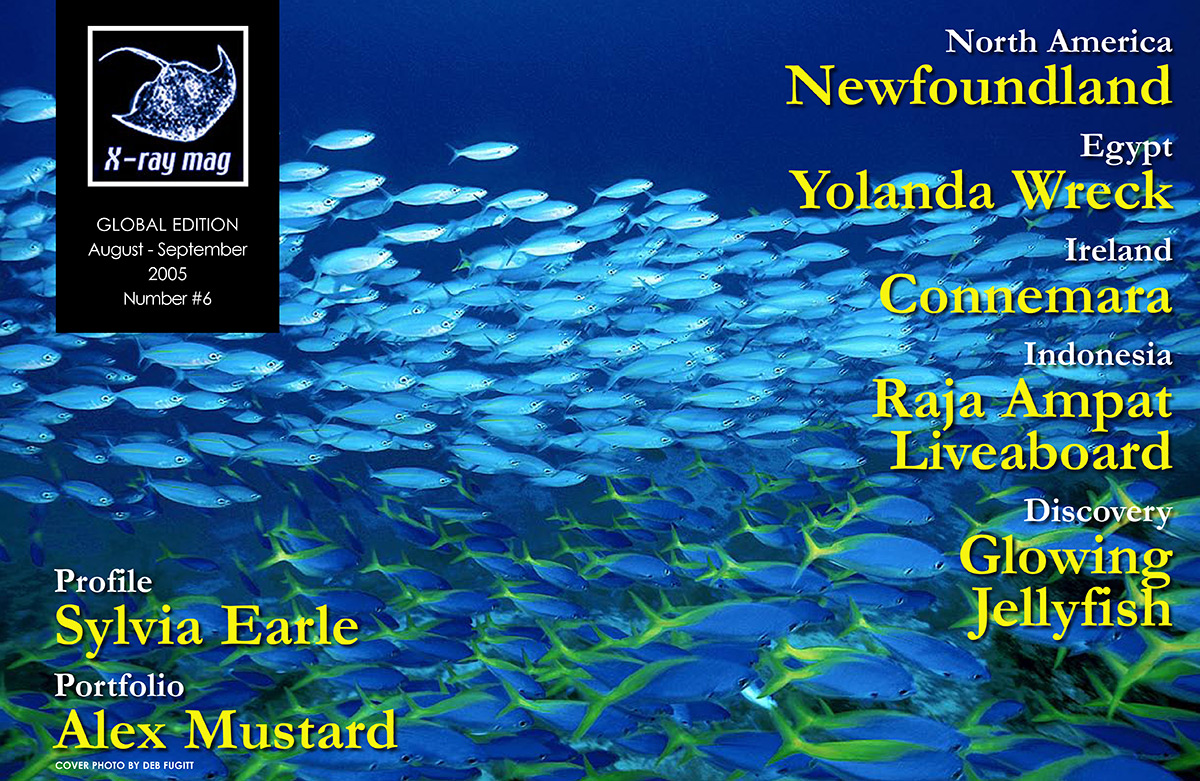

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #6

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #6

- Log in to post comments