U-Boat Navigator explores the Tragic Triangle of Valletta: HMS Russell, HMY Aegusa and HMS Nastortium

Contributed by

The U-Boat Navigator research vessel is known for its expeditions to the legendary HMHS Britannic (see X-RAY MAG issue #69¹) in Greece, but the company also does extremely interesting research in its “home” waters of Malta.

Malta, which is situated in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, always served as a crossroads of sea routes from Europe to Africa and Asia, and, over the centuries, witnessed lots of war activities, including both World Wars. Thus, there are a number of shipwrecks buried in Maltese waters, with only a few of them having been explored or even known to exist.

In reality, wrecks are the main attraction for divers visiting Malta—especially experienced technical divers, as the majority of the most interesting wrecks rests far below 40m deep. The most famous wreck is probably the 66m-long S-class submarine HMS Stubborn. Resting at a 56m depth, this vessel was a casualty of WWII. There is also the “modern” civilian vessel, the Imperial Eagle, resting at 42m, which was scuttled in 1999. Both wrecks lay several kilometers off Qawra Point. Another wreck worth mentioning is a WWII aircraft, the Blenheim bomber resting at 42m, which is located at Xorb l-Ghagin. These name just a few deep wrecks available to technical divers. (You can read more about recently discovered wrecks in Malta, such as the HMS Olympus² and a WWII submarine³, on X-RAY MAG’s website.)

Beginning divers can also find some remarkable wrecks to dive in Malta. For instance, there is a dive site with two tugboats—the St Michael and the Ten wreck. Both were purposely scuttled together in 1998 at Zonqor Point, and rest at a maximum depth of 21m. Or there is also a a shallow dive on the HMS Maori, which was the last Tribal-class destroyer to go to war in the Mediterranean. She sank in 1941, having been hit by a bomb, and now lies at 12m at the entrance of Dockyard Creek in Valletta.

Valletta – The Tragic Triangle

Valletta’s Grand Harbor is famous for its historical wrecks. And the fact that it is the home port of U-Boat Navigator does not mean that they are neglected. Every U-Boat voyage starts and finishes here. Indeed, the last part of the U-Boat’s 2015 expedition was devoted to the three local wrecks: HMS Russell, HMY Aegusa and HMS Nasturtium, lost 100 years ago, on the same day—27 April 1916. They all are also featured in the U-Film documentary project, Dark Waters, with the first episode of the series – “Red Cross on Water”—telling the story of the hospital ships during wartime.

When I interviewed historian Joseph-Stephen Bonanno at his workplace in St. Julians, he talked as if he was present during the events of days long past, as if he had participated in the marine operations and court procedures of the wrecks 100 years ago.

Bonanno said: “On the morning of 27 April 1916, Russell was heading towards the Grand Harbor. It was a bright day with a moderate breeze and a relatively calm sea. She arrived off Malta on the previous night. However, due to her late arrival, entry to the harbor was refused, because the boom defense had already been closed for the night, and the battleship was forced to cruise east of Malta.”

HMS Russell

HMS Russell was the first of six “Duncan” Class Dreadnoughts, which were constructed after Britain’s Naval Defense Act was enacted with the aim of overpowering all existing marine craft—especially the Russian “Peresvet” class ships, which were being built at that time. In an attempt to exceed the non-existing features of enemy battleships (which were found out later), HMS Russell was launched as the first of the Duncan class ships on 19 February 1901, with the following dimensions and specifications: 123.5m length between perpendiculars; 23m width; 7.8m draft and 14,000 tons of displacement; 18,000 horse power; and a top speed of 19 knots.

She was named after the Admiral Edward Russell, the 1st Earl of Oxford, who lived from 1653 to 1727. After changing fleets and captains because of changes in British marine policy due to dramatic fluctuations in relations with European countries during times of war and peace at the outbreak of the First World War, the Russell, together with her surviving sister ships of the Duncan class, were assigned to the 3rd Battle Squadron in the Grand Fleet.

Later, during the WWI, Russell served in the Dardanells, close to the Gallipoli Peninsula, within the British Dardanelles Squadron, and proved to be reliable and respected. At Gallipoli, she was among the last battleships of the British to leave the area. After the Gallipoli campaign was over, the Russell stayed on in the eastern Mediterranean.

“À la guerre comme à la guerre”—enemies, during war, will fight with every available means. Indeed, the Germans tried to make the most of their submarine fleet advantage and were successful. It was the submarine, SM U-73, that especially brought a lot of trouble to the Mediterranean.

The U-boat arrived off the coast of Malta on the night of 25 April 1916, and by midnight, it was located off the entrance of Valletta Harbor. By 1:40 a.m., the submarine’s crew had managed to place 22 mines, and then disappeared.

Russell was the first to hit one of the mines early the following morning on 27 April 1916 and sank, killing 124 people—mostly officers and crew members. But the terrible war demanded new victims that day!

Today, the Russell lies upside-down in approximately 115m of water, and would never have come back to historical light, if not for the group of technical divers who first visited the wreck in 2003. Now it is one of the regular sites for the U-Boat Navigator, whose crew has been filming the wreck for several years now. Every new immersion at the site is a reason to commemorate the memory of the HMS Russell crew.

HMY Aegusa

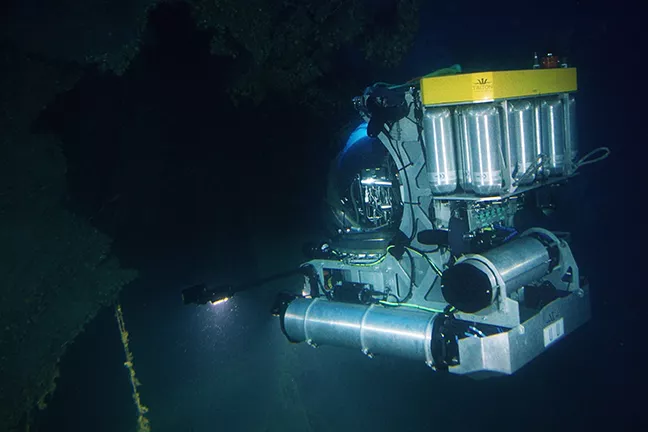

HMY Aegusa was the object of U-boat Navigator’s last submergence in 2015, on the 23rd of December. The dive with the submersible Triton 3300/3 was supervised by archaeologist Dr Timmy Gambin from the University of Malta. It was his second visit to the wreck. The very first dive, when the ship was discovered, took place in 2014.

The Screw Schooner Aegusa was built in 1896 in Scotland as a luxurious boat, one of the largest yachts of the time. She was 257.7 feet long, 31.65 feet wide, with a 18.5-ft draft. Besides that, she reached 16 knots in speed. Nevertheless, when the vessel was bought by Sir Thomas Lipton (remember the tea!) in 1899 as a tender for his racing yachts, she was reconstructed and redecorated in unbelievable luxury, including a mechanical piano in the music room, oriental art, paintings and porcelain worth a fortune, as well as collection of wines and spirits.

The ship, renamed “Erin”, hosted nearly every royal personality, or very important person, of the time, espousing the vanity of her owner. But after WWI began, the vessel—returned to her previous name of HMY Aegusa—began serving the British Red Cross Society, was re-equipped as a hospital ship and marked with red crosses. Later, she was armed to serve as a tender to several larger ships, and her final mission was to patrol the waters of the Mediterranean, watching for German submarines near Malta.

She struck a mine on the same unlucky day of 27 April 1916 while trying to save surviving crew members of HMS Nasturtium, and sunk within just seven minutes. The majority of the crew managed to abandon the vessel, but six of Lipton’s former crew members lost their lives with the explosion.

HMS Nasturtium

HMS Nasturtium was one of 36 Arabis class sloops built under the Emergency War Program for the Royal Navy in World War I, to be used as smaller anti-submarine vessels. She was launched on 21 December 1915 from one of the Scottish shipyards and had the following dimensions and specifications: 81.6m length, with a displacement of 1,250 tons, 3.58m draft, a maximum speed of 15 knots, and was designed to carry 79 people on board.

HMS Nasturtium served in Malta, but for just a short time. On the same black day of 27 April 1916, she was searching for enemy U-boats south of the island of Malta, not yet aware of the HMS Russell tragedy and the dangerous mine-fields.

HMS Nasturtium continued her duties, when at 7:55 p.m., she hit a mine herself. The five stokers lost their lives immediately with the explosion. The rest of the crew was rescued by oncoming vessels, including HMY Aegusa. Along with the ship’s engineers, the captain continued to fight for the vessel, but it finally sank later that night.

The story of Nasturtium and the U-Boat Navigator is not over, as the wreck that was considered to be Nasturtium turned out to be another ship, similar in size and shape. So what kind of ship was it then, that was found? And where is the real Nasturtium? These questions are yet to be answered in the upcoming expedition of the U-Boat Navigator team in 2016.

Revealing history

With the new underwater photography and videography gathered by U-Boat Navigator, which proves theoretical conclusions of historians, one more chapter of WWI history has been revealed. U-boat Navigator, according to David Concannon—Vice President for Flag and Honors of The Explorers Club, who was on board in 2015—is “one of the three best vessels in the world for underwater research”.

This year, U-Boat Malta LTD. added a new “toy” to their already impressive array of equipment, which includes the Triton 3300/3 submarine that dives from three to 1,000m with three persons, the ROV Ageotec Perseo GTV, all kinds of sonar—not to mention dive equipment covering all technical diving needs, including a hyperbaric chamber. This new toy is a Triton 3300/1 MD—a solo submarine with minimal displacement and weight, capable of working at 1,000m of depth. It was constructed by world-famous Triton Submarines especially for U-Boat Malta, according to the crew’s special request and technical specifications, and got wet in real conditions this season.

It is yet another technical step by U-Boat Malta to not only penetrate, but to work reliably in the depths of history. Most likely, the 2016 season’s expeditions will allow new wrecks in the depths to come to light and arise from oblivion. ■