Trading and transport by sea goes back to prehistoric times. Stone Age settlements and canoes, Viking ships, medieval cogs, fluyts, tall ships, warships, defence systems, jetties, harbour installations and aircraft wrecks—Denmark has got it all.

Contributed by

Factfile

A Visit to the Viking Ship Museum

Text by Catherine GS Lim

Vikings. As someone who grew up surrounded by sedate concrete buildings in a meticulously planned urban environment in Singapore, I knew very little about them. I had never learnt about them in school, nor were they part of my usual literary diet (well, barring Hagar The Horrible).

Thus, as the car I was in neared the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, I felt some degree of agitation. Was I headed for an afternoon filled with crippled ships with broken masts, long cannons and bloodied chainmail? (Hmm, it seems that I had somehow acquired an impression of Vikings being the sort to go around raiding villages in the countryside. I wonder how that happened…)

As soon as I stepped onto the museum premises, the atmosphere was serene and peaceful, yet with an air of excitement and anticipation. Under a cloudy sky, a breeze from Roskilde Fjord brought forth a welcoming whiff. I spotted a boat with a high mast stationed nonchalantly in the waters.

It was fully intact with zero battle scars. Feeling slightly confused, I entered the museum building.

Five Viking ships

The Viking Ship Museum houses the remains of five ships that were deliberately sunk around 1070 to serve as a defence against enemy forces and to block the fairway. Known as the Skuldelev ships, they were excavated in 1962. Today, around 950 years later, they serve as a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the Viking people.

To think that such massive (and sturdy!) ships could be built using simple hand tools without any Industrial Age machinery. And that the hulls of the ships (barring some missing strakes and disintegrated wood portions) were still fairly intact to this day… To say that I was amazed was an understatement.

Viking life

As the afternoon drew on, I learnt more about the living conditions on the ships and the life within the Viking community. I ventured out into the outdoor yard where visitors could try their hand at the different shipbuilding techniques. All aspects of seafaring and shipbuilding were covered. There was even a replica of a Viking ship that one could hop on (I did!), and possible sessions to actually ride on (read “row”) a Viking ship.

As I left the Viking Ship Museum that day, I came away with a new respect for the Viking people. They were a fearless and proud seafaring people, a strong innovative community with deep-seated values of family and kinsmen. Yes, there were warriors, raiders and conquerors, but beside them lived tradesmen, merchants, farmers, hunters, mothers, fathers, children… just like any other well-developed and structured society. ■

Archaeology is concerned with the excavation, surveying and protection of historical artefacts, both on land and under the sea. The findings provide an important key to our understanding of shipbuilding traditions, trade and life in the past, and political and military confrontations.

Two important and frequent types of finds made underwater in Denmark are Stone Age settlements and shipwrecks. Denmark has been populated since the glaciers retreated after the last ice age. At that time, the geography was much different, and the country was unrecognizable from the outline it has today. Nine thousand years ago, the sea surface was 30m lower than it is today because of the ice age.

What is now the Danish west coast and eastern North Sea shoreline was connected to Britain as big swathes of the North Sea were dry land that was settled by Stone Age communities as described in our feature “The Drowned Lands of Doggerland,” published in issue #61. At that time, the Danish Straits did not exist, as the Baltic Sea was a freshwater lake until 9,500 to 8,000 years ago, when rising sea levels broke through the Dana River, forming the Great Belt.

But as long as people have lived in these changing landscapes, they seemed to have predominantly settled along coastlines and been occupied with hunting and fishing. It also appears that their main mode of transportation was by water.

Around 7000 BC, the ice melted rapidly. Coastal settlements were flooded and were gradually covered by protective layers of sediment, providing good preservation conditions for tools and other artefacts of perishable materials. That is why many well-preserved items of wood are found underwater, whereas they are seldom preserved on land. Hence, a large part of the cultural heritage has been found underwater where artefacts have lain protected in the seabed, often for millennia, awaiting their discovery by professional or amateur archaeologists.

Archaeologists estimate that the remains of some 20,000 Stone Age settlements are to be found in Danish coastal waters. Many such settlements have been found during field surveys conducted prior to extensions of ports, the building of bridges and other infrastructure projects. For instance, one was found right under the most popular beach in Copenhagen, Amager Strand, and recently, another one was discovered right outside the leisure boat marina in Tuborg Havn (harbour). Other surveys, such as the transects performed prior to laying down cables or pipelines, have often also stumbled right into ancient wrecks.

Protected artefacts

Stone Age settlements, shipwrecks, defence systems, jetties, harbour installations and aircraft wrecks are artefacts of great historical importance and are therefore protected under the Danish Museum Act. As such, it is exclusively professional marine archaeologists from the museums who may investigate and excavate submerged relics. Everyone else may only observe and take photographs but not touch them.

To a large extent, this requirement just makes sense. But the rigid way it has been interpreted or administered in the latter years has prevented qualified members of the engaged amateur archaeological community to continue to assist and work under the supervision of professional archaeologists and museums. As there is a dire shortage of professional underwater archaeologists, this has frequently also led to situations where amateur archaeologists were left frustrated that they were not allowed to salvage artefacts, which have become exposed and at risk of destruction.

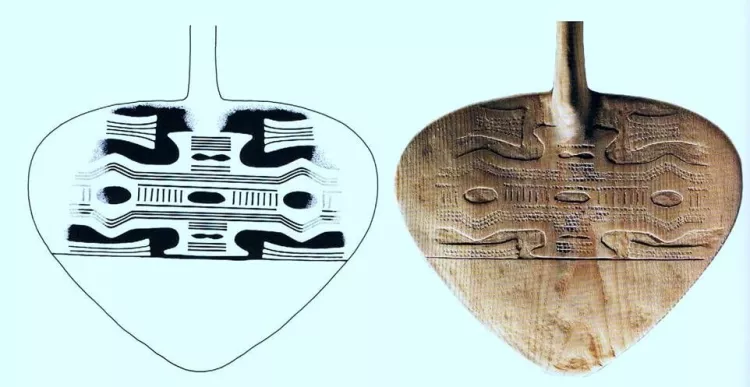

Marine Arkæologisk Gruppe (Marine Archaeology Group) is such a group of dedicated amateur marine archaeologists, which deserves a special mention in this regard. It is a dive club based in the town of Kolding, and one of the member clubs of the Danish Sportdiver Federation (DSF). This group, which has extensive expertise and experience in this field, has over several decades made several significant archaeological findings, which have been described in the relevant peer-reviewed scientific journals. For example, it was their discovery that Stone Age canoe paddles were decorated with intricate patterns.

Finds in Eastern Denmark

In the eastern part of Denmark, it is the Viking Ship Museum that holds the responsibility to safeguard all archaeological artefacts and to conduct surveys and excavation of sites of interest.

The direct route between Copenhagen and Germany is a road and rail link that crosses Storstrømmen—a strait between the islands of Sjælland (Zealand) and Falster. The old bridge that carries the railroad over the strait dates from 1937 and is about to be replaced with a new bridge, which will cross an area where important finds have been previously made.

Archaeological investigations soon discovered an 8,000-year-old settlement under 5m of water in Storstrømmen, with large quantities of rare artefacts and exceptional preservation conditions. When the settlements were inhabited, Storstrømmen was a deep valley with running streams and wetlands, and the maritime archaeologists found a rich assortment of animal and fish bones that indicated that people lived on resources from both the forest and the sea.

In conjunction with the same investigations prior to the construction of the new bridge across Storstrømmen, a Medieval ship from the 13th century was also discovered, which may provide a missing link between the slender Viking ships and the bulkier vessels of the Middle Ages, which could carry more cargo.

Farther south and along the same road and rail link to Germany, a tunnel is to be constructed across Fehmarn Belt connecting Denmark and Germany, which will replace the current ferry link between Rødbyhavn and Puttgarten.

Battle of Fehmarn wrecks

Already during early surveys in 2012, archaeologists discovered the wrecks of Lindormen and Swarte Arent—both lost during the Battle of Fehmarn (1644), which took place northwest of the island of Fehmarn. It was in this battle that a combined Swedish-Dutch fleet resoundingly defeated a Danish fleet. The Danes lost twelve ships, of which ten were captured.

The Swedish fire ship Meerman was sent against the Danish Lindormen, which quickly caught fire and exploded. Swarte Arent was a Dutch ship and the only vessel that the combined Swedish-Dutch fleet lost. Both wrecks have been located at a depth of 24m in the middle of the Fehmarn Belt and were found to be in “excellent condition.”

In more recent years, yet another shipwreck from the Battle of Fehmarn—the remains of the long-lost Danish warship Delmenhorst—have been discovered in just 3.5m of water and just 150m from the shore of the southern coast of the island of Lolland in Denmark. It is the last Danish sunken ship missing from the fateful battle. The Delmenhorst was intentionally grounded near Rødbyhavn, in the final hours of the battle, because the Danes hoped to defend it using a massive cannon in the harbour town.

These finds are but examples of the sites and wrecks that have been discovered during field surveys taking place ahead of just one infrastructure project. ■