German ocean liner General von Steuben was torpedoed by a Russian submarine in 1945 taking thousands of refugees fleeing the advancing Red army with her to the bottom. She now rests at 72 meters in the Baltic Sea making it one of the most impressive Baltic wrecks and daunting technical dives.

Contributed by

General von Steuben (GvS) was built in 1923. A modern ocean liner for the time, her top speed was 16 knots and she took 1100 passengers. With a weight of 38 500 tons distributed over a 168 meter long hull and a nearly 20 meter wide deck she was often referred to as “The beautiful, white Steuben” in advertising material from that time.

As it happened, GvS was the first German commercial ocean liner to port in the US after the First World War, opening the trade over the Atlantic once again. No one then knew what fait awaited her and her passengers.

The collapse of the East Front

During the Second World War many commercial ocean liners were requisitioned for military service as transporters. The fighting on the East front was particularly nasty. The German campaign in Russia had soon erupted into an incredible carnage, violence and terror so when the tide turned in 1943 the Russian soldiers were eager for revenge. As far as they were concerned the only good fascist was a dead fascist. Civilians, women and children making little difference. In retrospect, none was better or worse then the other.

It was war. The stakes were high. The sheer fear of the Russian army among the German civilian population who now found themselves at the front line was enough to make whole families commit suicide in some areas.

As the German front retreated the situation was desperate. Several hundred thousand civilians needed to be evacuated to avoid the advancing Russian 9th Army. So what did the German military command do?

The beginning of the end

The ocean liners General von Steuben, Wilhelm Gustloff and Goya were given the task to evacuate wounded soldiers and civilians and rescue them from the wrath of the Russian army. But the risk was immense as the Baltic Sea was dominated by Russian submarines. That the superior speed of GvS was sufficient to outrun these submarines was, in a sense, a correct assumption.

However, as this was not the case for escort ships these, in this case, represented the weakest link in the chain. One of them had a much worn down insulation in the chimney and running on steam it generated sparks which were visible at great distances at sea, regardless of the blackout routines practised onboard at the time. Alexander Marinesco, captain of the Russian submarine S-13 soon spotted the sparkling lights on the deck in his binoculars.

The End

At 00:52 two torpedoes struck the starboard side. General von Steuben had 5 decks; the lower was completely filled with immobilized wounded German soldiers. Before leaving from Pillau General von Steuben was overloaded with people who wanted to escape the Russian Army.

Built for 1100 passengers, she now held nearly 5 000 passengers. This sheer number of people onboard meant several children was born onboard every day. As the most of the crew quarters were located exactly where the torpedoes hit, any organized effort in handling the emergency was crippled from the onset. Panic ensued.

Only 659 people survived in the 4˚ C cold water and by 01:32 General von Steuben was gone from the surface.

Sentiments

Sitting on the aft deck of the dive vessel Moskus brings many thoughts and sentiments to mind. While one part of you is exhilarated about the adventure lying ahead another significant part of you is intensely focused on the concrete dangers and challenges ahead.

You try to be very methodical, calm and focused on relaxing. It may sound easy but donning all that equipment is very symbolic. Many technical divers, therefore, rely on ritual routines to prevent mistakes and alleviate stress prior to the dive.

If you are already stressed before you leave the surface one thing is certain; it is not going to get better once you dive. Being in a hurry is simply lethal. The biggest challenge is faced by the divers going down on the wreck first. T

hey don’t know what they are going to face, or whether it is possible to successfully attach the downline to the wreck – which is a requirement in order for the dives to proceed in a safe manner. In my case, I lie on the surface while my pulse gets back down to its normal resting level. My breathing becomes a central aspect in controlling the mental state.

Going down

I breathe with long calm breaths. The downline goes straight down into the darkgreen haze. I start pulling myself gently down by the line while I routinely monitor all my equipment. The computers are working, the lamps are functioning, the rebreather is doing what it is supposed to do and the suit isn’t leaking. Everything is AOK.

At 20 meters the light gets dimmer and the temperature drops steadily. After four minutes I find myself at 40m but I still seeing nothing ahead of me but the beam of my dive lamp. Am I heading straight into a big fishing net? Am I running into a current? How is the visibility?

After seven minutes I finally see the outline of the hull. The sound of breathing penetrates my mind. In the twilight, all kinds of visualisations and fantasies seep into my mind. “Is that a net?” The visibility is quite good. This is very important and I am pleased. As I don’t have much experience diving to these depths and this alien environment I would have aborted the dive in case of bad visibility.

Suddenly I get this feeling of being a trespasser in a cemetery. This isn’t all that great. I am terrified. Everything worthwhile living for is up at the surface, so what am I doing down here?

It is the helium enriched breathing gas that makes my fantasy overactive. After a couple of minutes, I manage to get my composure back and feel like continuing the dive. The downline is like an umbilical to life. If I am unable to find it again the risks associated with this dive will suddenly rise exponentially.

Every fin stroke which takes me further away from this exit point has consequences. It is important to be present. Over the port bridge wing I spot a big cod being caught in a net. It is struggling. Once again a fear of becoming entangled in the net myself creeps in on me. There are plenty of nets on this wreck as it has been down here for 60 years.

Experience matters

I signal my buddy Larry that I am uneasy. We haven’t had many dives together and there aren’t many people around in this county doing these kinds of dives in the first place. But we have spent a fair deal of time together on the dive vessel Moskus, enough to establish a trust in each other. Larre is very experienced, which is comforting for me who is not.

The cold is starting to make itself felt and time is ticking away. I was at the downline at 50m after seven minutes and at the bridge at 65m after 15 minutes. The cold makes me lose the sensation in my hands. We read each other's eyes and movements in the water. The trepidation from being in a graveyard won’t let go. I didn’t expect it to feel like this. I feel perturbed, get philosophical and start thinking intensely about my family, my wife and my children.

Focusing

I focus once more on my breathing. Now I start longing after seeing the downline again. This dive has been very demanding. The thousands for hours spent underwater is starting to pay off though. I am calming down. I see a boot lying beside the engine-room telegraph at 65m. I take a look at the bridge. It is in a vertical position, the door is like a windbreak. I can’t enter with all my tanks, it is too narrow.

I am aware that more dives are possible and that time is now against us, and I decide to turn around and head for the downline. After 25 minutes we are back at the downline as planned. Ahead of us waits one hour of decompression during which one can ponder a lot on life.

Each diver seems to be engrossed in his own thoughts busy with the dive computers, changing gasses and timing each stop. The water gets warmer and the light and hope return. Once all the divers are gathered aboard Moskus we start comparing experiences and information constructing a joint picture of the circumstances down there.

The next dives take on a different character of a somewhat more intellectual flavour. The trepidation I experienced during my first dive recedes and armed with more information and confidence it becomes possible to perform more advanced dives later on. We stay on-site for three days and dive twice a day. That is all you can cope with mentally and physically. Many of the divers have a passionate relationship with vessels and their construction and find each ship has a personality, a soul.

General von Steuben was“ the white beautiful Steuben” as it was promoted in the days when she served as a liner. Now she sits like a church on the seabed. As far as I am concerned I was tested to my limits.

But what I have witnessed and the experiences I can now share with a wider audience will hopefully help to remember the incredible suffering the second world war brought upon so many people. We now have something in common on board. Humbled by the experience, we have found a new respect for life and for pulling this venture off together.

Rediscovered after 60 years

Until 2004, the exact location of General von Steuben’s was unknown. Discovered by Swedish company “Marin Mätteknik” and Deep Sea Production, a Swedish film production company she re-emerged as a dot on the GPS once again. National Geographic were quick to fund a Polish diving expedition and others soon followed.

Issues

General von Steuben rests in international waters and the legal aspects of accessing the wreck are not well defined. Ethically the issues are more troublesome. How long is long enough to allow divers to enter what is a grave?

Ask different divers and you will get different answers. For those with national, cultural or family ties to the wreck such activities stirs strong emotions. For those with a profound interest in contemporary history, naval design and technical diving the perspective is a different one.

It is all about perspective but if one can show respect and understanding for fellow human beings it helps, no doubt.

Swedish diving expedition to General von Steuben

Our dives took place in July 2005. With the Swedish diving vessel “Moskus” and Captain Tobias Åberg, our resources were somewhat limited compared to the extensive Polish expedition which featured large ROVs, decompression chambers and other goodies on a 100-ton commercial diving vessel.

The Swedish diving vessel “Moskus” being smaller, no less offered all needed for men with courage. Yes, the stories after National Geographic featured their article was that General von Steuben was covered in nets, after 60 years of fishing in the Baltic. As locals, we knew that this is true for most wrecks in these waters.

However, dropping the anchor on an echo and seeing Tobias Åberg and Peter Oleander descending down to secure the anchor line and decompression line on the wreck left us concerned for a while. More then one diver has perished in fishing nets in the Baltic.

Anchoring

Tobias and Peter are experienced with more the 1000 hours each in these waters. After 80 minutes they surfaced. We learned that our anchoring point was just below the bridge. The hull located at 50 meters and the bottom at 72 meters with the number of fishing nets being a concern to us.

Darkness prevailed at these depths, but visibility was good with no currents present. With winds of less than 4 meters per second and nearly dead calm conditions at the surface, the conditions were excellent, which is very rare in these waters. The Baltic Sea is generally a shallow basin so winds above 6-8 meters per second immediately generate very rough conditions at the surface.

Technical aspects

Our dives were based on using CCRs, mostly Inspiration, KISS and MK15 units, VR3 computers and trimix with 10/50 mixtures for bottom gas, partial pressure of oxygen set to 1,2 Bar and some of us had 4th oxygen sensor and real-time tracking of actual gas mixture for the basis of decompression.

The nets were fought with conventional tools, but the water temperature and the penetration dives were too much for our digital video equipment. Read more details and see more images from the expedition on www.cortex.se. (link)

Diving General von Steuben

The Baltic Sea provides very varying diving conditions. One day is never like the other, even on the same location. During summer, the algae are blooming and this reduces visibility quite considerably, especially along the coasts. In open sea visibility usually improves a lot with depth. This is quite paradoxical as the sun doesn’t penetrate further than 30-40 meter, even in blue sky conditions.

I rested on the surface and waiting for my pulse to come back down after all the preparation and dressing up under the burning sun on a 25° C hot day wearing nearly 80 kg of diving equipment before I turned on the lights and monitored my oxygen sensors. Descending I turned the rebreather to high-set point of (1.3bar) pp02 and filled the suit with gas. 40 meters time was reached 5 minutes into the dive. We had intentionally a short anchor line to reduce decent time to a minimum. Our decompression line was separate from the anchor line. A good thing at times of unstable weather conditions. It was dark now.

Partial pressure

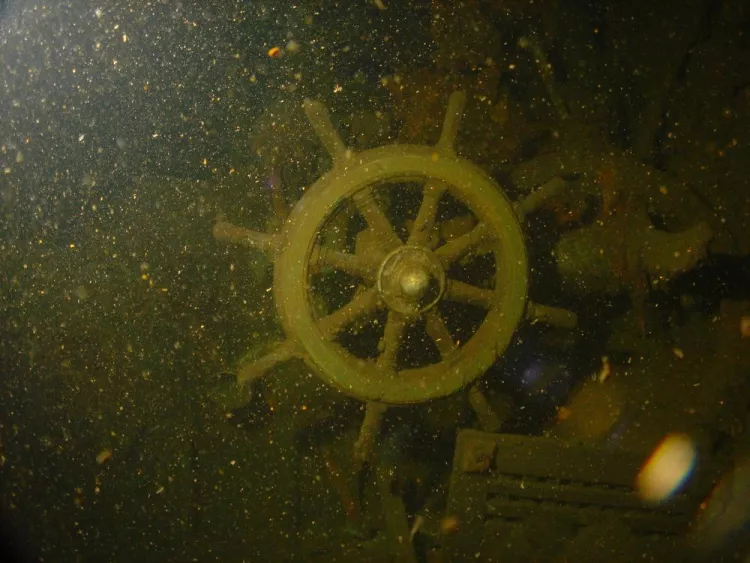

The partial pressure was holding stable much thanks to the ADV. (Automatic Diluent Valve that equalises the counterlungs on the rebreather, ed.) Lights were good. Visibility was excellent! I noticed the portholes at 45 meters and touched the hull. Leaving an 80 cc bottle 50/50 mixture for backup on the line. Larre Ländin, my diving buddy and I both noticed the bridge from the drawings we had on General von Steuben.

Leaving the starboard bridge and descending to 55, 60, 65 and 68 meters we found ourselves five meters above the bottom. General von Steuben is resting on her port side, tilted more than 90 degrees.

A great deal of debris and nets are located on the port side. We looked straight up into the bridge, which was all intact. Very few divers had been here. The previous expeditions had done a lot of penetration dives. Lines into the ship were obvious and observed from several other diving colleagues who did other tours on the wreck.

Time was now 18 minutes, and we realized that we needed to return to the ascent line to follow or initial dive plan. The sensation was that of entering a relic of the tragedies that took place here. We felt uncomfortable at times and avoided penetration dives initially. The cold water was also affecting us and the expectation, anticipation and preparation started to take out its toll. In the later dives, we did pursue deeper penetration dives, much forced upon us by appearing underwater currents.

General von Steuben is extremely spacious and excellent for penetration diving. However, due to its awkward position, it is difficult to maintain a good sense of location and the size does influence the perception and attitude regarding bottom time. We went from doing profiles 65 m and 25 minutes bottom time to doing 70 m for 40 minutes bottom time. After 3 days most of us was mentally and physically exhausted.

Blurred vision & Hallucinations at 70m

Being a landlubber, going out on the Baltic Sea usually means having to use some kind of motion-sickness medication. Most divers have been told about the side-effects of medication will be altered with increased pressure, most common relating to drugs which will alleviate swollen mucous membranes in the upper airways and problems to equalize, which we all know is contraindicated and relates to risks of a reverse block and ruptured tympanic membrane (ear-drum).

With motion sickness, the use of scopolamine, an anti-cholinergic substance has been gaining use since the introduction of transdermal patches which permitted slow release over 72 hour period. However, side effects such as impaired accommodation (blurred vision), bradycardia (slow heart rate), reduced salivation still are very much side effects despite the mode of distribution.

Desorientation

Another aspect which technical divers need to take into consideration is that an unusual but reported side effect of scopolamine is “disorientation, anxiety and hallucinations” in less than one out of thousand cases. Not a good thing to experience such side effects when reading your diving computer at 70 m in 4° C pitch-black water.

Add to this the combination of trimix gases and the lack of mental sedation which nitrogen otherwise brings (which we, of course, do not want). The combination of trimix gases and medications at partial pressures well above normal levels speaks it own language. Very little research has been done, preclinical and in laboratory environment only. No case reports have been published.

Personally as a physician and starting out as a technical closed circuit rebreather diver with the aim to take pictures of the wreck General von Steuben, I found after comparing my experiences with my dive buddy back at the surface that I have had visual hallucinations and that my footage and video from many dives were out of focus, as I thought my mask was fogging up on me as it might have in previous thousands of dives I have done.

Lesson learned

Scopolamine transdermal patches and trimix diving is not an acceptable combination. Not all will hallucinate, but the compromise if you have to travel great lengths at sea before reaching a destination is to put these patches on 4-6 hours before trip starts, and remove them 12 hours before diving.

Better still is not use these at all, stick to antihistamines drugs of newer types. Ask your doctor. It is plausible that pressures above 5 bar along with trimix gases potentiate and increase serum concentrations that might give a higher frequency of reported side effects. Better safe than sorry. Task load is enough with CCR, trimix, Baltic Sea deep diving and videocamera as it is more than so often.

Summary

We did penetration dives into the General von Steuben and saw many things, which we out of respect for the readers and relatives do not speak about or have taken pictures of. Over 4000 people rest here, and we have not disturbed them. We think of it as visiting a gravesite.

She is very intact, has tremendous spacious internal areas that provide excellent, world-class penetration dives. If you have the opportunity and have the skills, equipment, experience and crew needed this is a wreck you have to dive.

But read up on your knowledge of the 2nd world war, share it with others and have a deeper more meaningful experience than just another logged dive. This site demands a humble approach, as is true with many physical and psychological challenges in life.

Additional links

Swedish diving vessel “Moskus”in Ystad, Sweden. www.moskus.se

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #8

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #8

- Log in to post comments