Separated from the northern coast of mainland Scotland by only the six-mile-wide channel of the Pentland Firth, Orkney has some 90 islands, only 18 of which are inhabited. In the southern region of the archipelago is the large area of sheltered water known as Scapa Flow. Scapa Flow was the base chosen by the British Admiralty as the home of the Grand Naval Fleet.

Contributed by

Factfile

Lawson Wood is from Eyemouth in the southeast of Scotland and has been scuba diving since 1965.

With over 15,000 dives logged in all of the world’s oceans, he is the author and co-author of over 50 dive books.

He made photographic history by becoming a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and the British Institute of Professional Photographers solely for underwater photography.

He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, a co-founder of the first marine reserve in Scotland and a co-founder of the Marine Conservation Society.

This deep, formidable, cold, natural harbour has served the warring nations’ fleets since the time of the Vikings, the Knights of St. John, the Spanish Armada and the American War of Independence. Scapa Bay was also the rendezvous point for merchant ships en route to the Baltic Sea during the Napoleonic Wars from 1789 to 1815.

Graeme Spence, maritime surveyor to the Admiralty, said in 1812: “… the art of Man, aided by all the Dykes, Sea Walls or Break-Waters that could possibly be built could not have contained a better Roadstead than the peculiar situation and extent of the South Isles of Orkney have made Scapa Flow . . . from whatever point the Wind blows a Vessel in Scapa Flow may make a fair wind of it out to free sea . . . a property which no other Roadstead I know of possesses, and without waiting for Tide on which account it may be called the Key to both Oceans.”

History

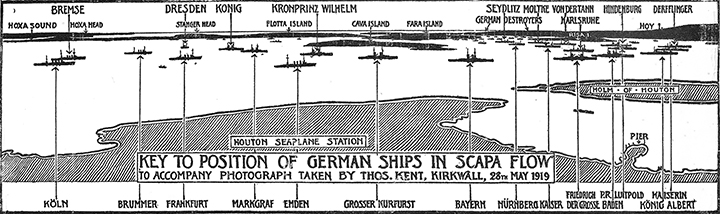

After a rather confusing end to the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916, when 25 ships were lost from both sides and with both navies claiming a moral victory, the German fleet returned to her home bases at Kiel & Willhelmshaven and languished under extreme duress until the end of WWI. As part of the terms of the surrender, it was agreed that the entire German High Seas Battle Fleet (except the submarines, which went to Harwich) would be interned at Scapa Flow until the Allies could make a decision as to their fate.

The Orcadians were no strangers to large numbers of ships on their doorstep, but on 23 November 1918, they woke up to witness the greatest naval spectacle ever seen on the planet. Almost the entire naval fleets of both Germany and the United Kingdom were at anchor in Scapa Flow. When you consider that the population of the islands numbered around 20,000 at the time, this huge combined fleet manned by over 70,000 naval personnel and 74 German ships, which included its 11 best battleships and all six of its battlecruisers.

Time dragged on and many of the disgruntled German Navy’s crew were moved to detention camps before being repatriated. Taking advantage of the internment to save the Imperial Fleet from further disgrace and not having been informed properly over the reasons for the Armistice being surrendered on 21 June 1919, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter was convinced that war conditions were to be reinstated and that his fleet was to be used by their enemies against their homeland. The German Commander thought that the Treaty of Versailles would leave them with little choice but to scuttle their own fleet, lest the Allies get their hands on an entire navy.

Whilst (coincidentally) virtually the entire British Navy left Scapa Flow on exercise on Midsummer’s Day in June 1919, Admiral Reuter sent out a coded message to his entire fleet (this coded massage was actually delivered by a British dispatch tender!). This message instructed each ship to open their seacocks, break all valves and scuttle the entire fleet.

Much to the astonishment of a party of Orcadian schoolchildren who were on a field trip that day, they watched the German crews whooping and shouting for joy as they made off in small boats from the sinking fleet. This culminated in the largest intentional sinking in worldwide naval history, where over 400,000 tons of modern shipping was lost that day. The British Navy were immediately alerted, returned as fast as possible and even managed to beach a few of the smaller ships; however, the fleet arrived too late for most of the sinking.

Salvage

It did not take long for the locals to start that “diving lark.” Seeing the potential for some easy scrap metal, the first salvage company started three years later by the Stromness Salvage Company, which raised the Light Cruiser G-89 off the Isle of Cava. They eventually sold this to Cox & Danks.

But before Frank Cox and his team moved in, the Scapa Flow Salvage and Shipbreaking Company opened for business in 1923 and initially bought four destroyers. They hoped to raise these ships by running hawsers under the hull, so that when the rise and fall of the tide raised them up sufficiently to get them off the seabed, the salvagers could pull them into shallow water. They would repeat the process until the ship was above the surface at low tide, where the water in the hull would then be pumped out and the vessel could float off easily on the next high tide.

However, before they could start this enterprise, Cox moved in with all of the equipment and personnel required to raise a fleet of sunken ships. Cox had earned his fortune and reputation in the scrapping of railway engines and quickly recognised the potential on offer in Scapa.

The greatest marine salvage operation ever undertaken on the planet was set to begin with quite exemplary and innovative techniques. This basically consisted of building huge towers, which were attached to the hulls of the upturned ships. The water in these tubes was then pumped out, and a hole was cut into the hull to allow the hard hat divers access into the wreck’s interior, where they proceeded in blocking off all the holes in the rest of the ships. Compressed air was then pumped into the hulls, filling the ships with pressurised air and simply floating them off the bottom. Employing this method, Cox & Danks raised the heaviest ships from the deepest water—and just about everything else in between!

Using equipment gained from Germany as part of the reparations for their “illegal” actions of sinking their fleet, Cox raised 32 ships in the next eight years. He then sold out to the Alloa Shipbreaking Company, which changed its name to Metal Industries and continued the salvage works from 1934 until 1947. Using the same techniques as Cox & Danks, Metal Industries even managed to raise the intact Derfflinger at 28,000 tons, which was the largest ship ever raised from the deepest water at 45m (150ft).

Arthur Nundy then took up the challenge in 1956 and systematically blew the guts out of most of the remaining ships to get at the valuable scrap inside. Unfortunately, he was the person responsible for the sad fate of the remaining deep battleships, which now have horrendous cavities in their hulls, resulting in the hastening of the deterioration of this once grand fleet. He finally sold out to Scapa Flow Salvage in 1972, which worked on the remains of the sunken fleet until the removal of the scrap became no longer viable.

Wreck legacy

Virtually all of the German High Seas Battle Fleet were subsequently raised and scrapped. But by the time the value of scrap metal had dropped, the state of the remains left behind were not worth further effort. Those that were left are what we all dive on now. This comprises the following:

- • 3 German battleships: König, Markgraf and Kronprinz Wilhelm

- • 4 battleship debris sites: Bayern, Seydlitz, Kaiser and von der Tann

- • 4 light cruisers: Brummer, Karlsruhe II, Dresden II and Cöln II

- • 1 light cruiser debris site: Bremse

- • 5 torpedo boats (small destroyers): B109, S36, S54, V78 and V83

- • 1 WWII destroyer: F2

- • 1 German submarine: UB 116

- • 17 large diveable blockships (out of 43 sunk): Tabarka, Dyle, Gobernador Boreis, Inverlane, Aorangi, Numidian, Thames, Minieh, Rosewood, Almeria, AC6 Barge, Emerald Wings, Ilsenstein, Martis, Empire Seamen, Reginald and Juniata

- • 47 large sections of remains and salvor’s equipment

- • Many other bits of unidentified wreckage and numerous small ships, supply barges and aircraft

What these erstwhile salvors left behind are now classified as national monuments and protected under the Protected Wrecks Act of 1973 and Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979. The two War Graves of HMS Vanguard and HMS Royal Oak are also protected under the Military Remains Act of 1986, and diving on these ships is prohibited.

Geography & wreck locations

Considered by many to be impregnable to attack, the bay of Scapa Flow covers some 311 sq km (120 sq mi) and is now almost totally landlocked with Mainland to the north; the islands of Hoy and Flotta to the southwest; and to the southeast, the Churchill Barriers link the islands of Lamb Holm, Glimps Holm, Burray and South Ronaldsay. This results in some relatively calm waters for most of the year.

The Churchill Barriers were built by around 1,400 Italian prisoners of war as a direct result of the attack and sinking of HMS Royal Oak in October 1939. They not only left behind a lasting legacy, which links all the southeastern islands, they also left behind their “Italian Chapel,” located on Lamb’s Holm, which is a must-see on everyone’s pilgrimage to Orkney.

The blockships sunk previously in the main passages into the Flow were designed to stop enemy ships’ movements, but they soon deteriorated under the constant battering of the fierce currents and tides into Scapa. The Churchill Barriers, of course, removed the need for many of the hulks. Subsequently, many of the ships had to be removed to make passage safer, undeniably making scuba diving in this area that much richer and more interesting.

The wrecks are actually dotted all over Scapa Flow, with blockships found in the extreme eastern and western areas of the Flow. The German light cruisers and battleships are found roughly in the centre of Scapa Flow, arranged in a horseshoe shape near the island of Cava and a rocky pinnacle called the Barrel of Butter. However, because the tidal streams which used to pass through the sound have been altered due to the construction of the barriers, Scapa Flow just is not as clear as one would like it to be, as the particulates in the water tend to stay in suspension for quite long periods, particularly after the algae blooms in the spring and autumn.

The natural harbour of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands has the largest concentration of shipwrecks in Europe. I am reliably informed that there was more scrap metal here in this confined space than in any other place on the planet.

Diving

For the most part, all of the diving is in open water, involving jumping off the side of a dive boat and swimming down a shot line, generally in water with poor visibility. However, there are a few locations in very shallow water where visitors can either scuba dive or snorkel on the remains of some amazing shipwrecks. For those who are unqualified, there are a couple of dive schools on the island. For many people, it is the shipwrecks of Scapa Flow that are part of their first diving experience.

Many divers still assume that one can only explore the German Fleet wrecks using nitrox, trimix or rebreathers, and that all of the wrecks should be treated as decompression dives, only to be dived by super-qualified “technical” divers. However, diving in Scapa Flow can be as simple or as complicated as you want to make it.

Novice divers can have a great diving holiday in Scapa Flow, and indeed, many visitors gain their first diving qualification through the excellent dive schools on the island. The shallowest part of the Karlsruhe is in only 15m (50ft), and the seabed is less than 30m (100ft) deep. All of the motor torpedo boats and blockships are in less than 18m (60ft). The blockships at Barrier II are at depths under 6m (20ft) and are quite possibly some of the best shallow shipwrecks in Europe. Therefore, all the blockships and German light cruisers are achievable for novice divers (under supervision).

A diving holiday in Scapa Flow is realistic for novice divers, as the diving on offer goes beyond mere opinion and expectation. Novice divers are able to dive alongside those super-qualified, mixed-gas divers on over 70 percent of the same shipwrecks.

Whatever your preferences are in diving standards, qualifications or preferred air mix, there is no denying the mystery, mystique and historical importance of the German High Seas Battle Fleet as well as the remains of the blockships. Thankfully, all of the ships are now protected and are regarded as national treasures for everyone to enjoy. While Scapa Flow is there to be enjoyed by everyone, please dive responsibly and please recognise that all of the shipwrecks have protected status under the Protection of Wrecks Act of 1974 and are scheduled under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979.

Recent discoveries

As the author of the Scapa Flow Dive Guide by Aquapress, the work never actually stops after the book has been published as there are always new and exciting discoveries to be made. Now, the 100th Anniversary edition includes new and important information, which has come to light through the additional extensive research of Kevin Heath and both of us painstakingly going through all of the archival photographs during WWI and WWII War Department records.

Heath in particular discovered in one instance, it would appear that back in 1914 when the Admiralty was sinking some of the first blockships in Burra Sound, they made a dreadful spelling error! This is not the first time that such mistakes have happened, as I found out doing my research on the book Shipwrecks of The Cayman Islands.

Back to Scapa Flow, and trawling through the National Archives in Kew and the Maritime Museum in Greenwich. We have discovered that there was no such ship as the Doyle. It is sometimes confused with the Moyle, which was a 1,761-ton, steel, 79.3m (260ft) long, single-screw coastal steamer built in Troon, Ayrshire, registered in Belfast. She was used as a blockship, but not in Scapa Flow. She was sunk in the approaches to Dunkirk on 4 June 1940. Ian Whittaker, who compiled the excellent wreck resource book Off Scotland, confirmed these details for me. That spelling error has contributed to the wrong name being used from the date of her supposed sinking in 1915. The ship that was actually sunk in Scapa Flow on 7 October 1914 is now to be known as the Dyle.

Dyle. Built in Newcastle by A. Leslie & Co. Engineers in 1879 for W. Johnson in yard No.209, she was sold to Turner Brightman & Co in 1886 and finally became the Dyle when she was subsequently sold to De Clerck & Van Helmeryk in 1902 and registered in Antwerp, Belgium. She was eventually sold to British shipbreakers in 1914, who resold her to the Admiralty for use as a blockship. Of iron construction with five bulkheads and a 177NHP two-cylinder engine and one propeller, she weighed 954 tons and was 260ft (79.25m) long.

Many regard the Dyle as being the best of the diveable blockships in Burra Sound. As the smallest of the three most intact blockships (the Gobernador Boreis and the Tabarka being the other two), the Dyle is completely open in aspect. Lying on her port side and fairly well embedded in the gravel seabed, her propeller is very distinctive, covered in miniature plumose anemones. Her wooden decks are long gone, creating easily managed swim-throughs between the supporting iron ribs. Both the bow and stern are relatively intact and topped with kelp, making for some excellent photographic opportunities.

Clio (I) and Clio (II). Other discrepancies have also occurred in the descriptions of the Clio (I) and the Clio (II) over at the opposite side of Scapa Flow at the Churchill Barriers. Both ships were thought to be steamers, identical in size at 2,733 tonnes, 70m (230ft) long, built in Hartlepool in 1889, but sunk ten months apart.

The records should now show the following:

- Clio (I): 2,733-ton steamer, 90m (300ft) long, built in West Hartlepool in 1889 and sunk in Water Sound on 29 April 1914. (She was scrapped prior to the construction of Barrier IV. She is confused with the identically named SS Clio that was sunk ten months later at Barrier III on 27 February 1915).

- SS Clio (II): 793-ton steamer 70.1m (230ft) long, built in Kinghorn in 1873 and sunk in Weddell Sound on 27 February 1915. (The firing circuit failed, and the Clio was swept out to sea. A wreck out to the east of Glimps Holm may be this ship. She is confused with the identically named Clio that was sunk ten months earlier at Barrier IV on 29 April 1914).

Cape Ortegal. Further research by Heath has now confirmed and cleared up some confusion over the blockships in Skerry Sound to the east of Churchill Barrier II. The wreck we assumed was the Cape Ortegal should now be recognised as the Almeria, as the remains on the seabed only show two boilers. The Cape Ortegal had three boilers. As the area where she was sunk was in the deepest part of the Skerry Sound channel, it looks entirely possible that the ship sank into the deepest part of the channel, similar to the fate of the Minieh to the west of Barrier I.

Through studying naval photographs and documents, Ordnance Survey and other aerial resources, the archives in the Orkney Library and newspapers, as well as all records held in the National Archives, we have discovered no evidence or records of the Cape Ortegal being scrapped for salvage, so we can only assume that she now lies directly underneath Churchill Barrier II, as no other evidence has been found—yet. A full survey of the substrata of the barrier is yet to be undertaken to confirm this, but the evidence at this stage is compelling for the findings.

Naja. In addition, over on the Churchill Barriers, we now have positive confirmation of the Naja! I had this blockship on Barrier IV that crossed Water Sound, identified as the Maja. Again, a spelling blunder led us all along the wrong path, and I have seen the same ship identified as the Nadja, Maja, Nada and the Madga in various books and periodicals. We can now confirm that this ship is the Naja.

We have her original bill of sale, how much she was then resold to the Admiralty for, how much Metal Industries charged the Admiralty for her sinking, her position and even a contemporary line drawing of the vessel in her eventual position. She was never salvaged and still lies beneath the ever-encroaching sands of Water Sound.

In the last few years, virtually all obvious signs of these once great blockships are now gone. The shoreline is now over 130m (400ft) farther out to sea, and sand dunes have covered virtually all of the ships, excepting for the bridge of the Collingdoc and a small part of the steel mast of the Carron.

Warwick aircraft. The Warwick aircraft, which ditched after engine trouble on 10 June 1944, was always a mystery. We searched for her relentlessly over several seasons near Lyness, on the Isle of Hoy, where she was finally found—or what was left of her remains. She actually ended up on the shore, and parts of her bomb bay are still underwater, but what was left on the shoreline was all salvaged.

TS37. Finally, a more contemporary shipwreck is located near Houton, to the northwest of Scapa Flow. A small fibreglass cabin cruiser with the registration numbers TS37 sank apparently in 1995; however, the photograph that we have managed to get from the Orkney Image Library was taken in December 1995. She once belonged to the late Kenny Bain and was driven ashore in bad weather. Subsequently towed off from the shore by a local pilot boat, she was so badly damaged that she sank on her way back to Scapa Pier. She is now lying on the bottom of the Flow, just off Greenigoe, in 29m (97ft) of water, relatively intact and upright on the seabed.

Undeniably, all of the ancient High Seas Battle Fleet are seriously deteriorating, but with due care and caution, there is no reason why we cannot continue to enjoy these superb shipwrecks in an area which can be dived all year round and suitable for all levels of divers. The shipwrecks of Scapa Flow are some of the most important historical shipwrecks accessible to divers in the whole of northern Europe, and the fact that we are still discovering information on their history is fascinating enough to make you want to go back and dive them all again. ■