The seas around Denmark have seen thousands of shipwrecks from ancient times until today. We take a look at a selection of wrecks from WWII minesweepers to WWI Battle of Jutland armoured cruisers to Age of Sail vessels with cannons.

Contributed by

Factfile

The Law Regarding Finds & Artefacts

Contrary to widespread belief, a wreck, its cargo and any artefacts that may be found on or around wrecks, always have an owner. There is no such thing as an ownerless or “abandoned” wreck. There are only wrecks for which the owner may not be known, or cannot be immediately identified, but in principle, somebody owns them. In some cases, it is an insurer.

Get permission: If a wreck is younger than 100 years, permission to retrieve “souvenirs” can be applied for on the Danish Maritime Authority’s website. (The form is in Danish, sorry). Retrieved artefacts may not be sold. Wrecks and sites that are over 100 years old are protected under the “Museum Law,” and artefacts may not be retrieved. This includes loose or detached objects laying on the seabed. ■

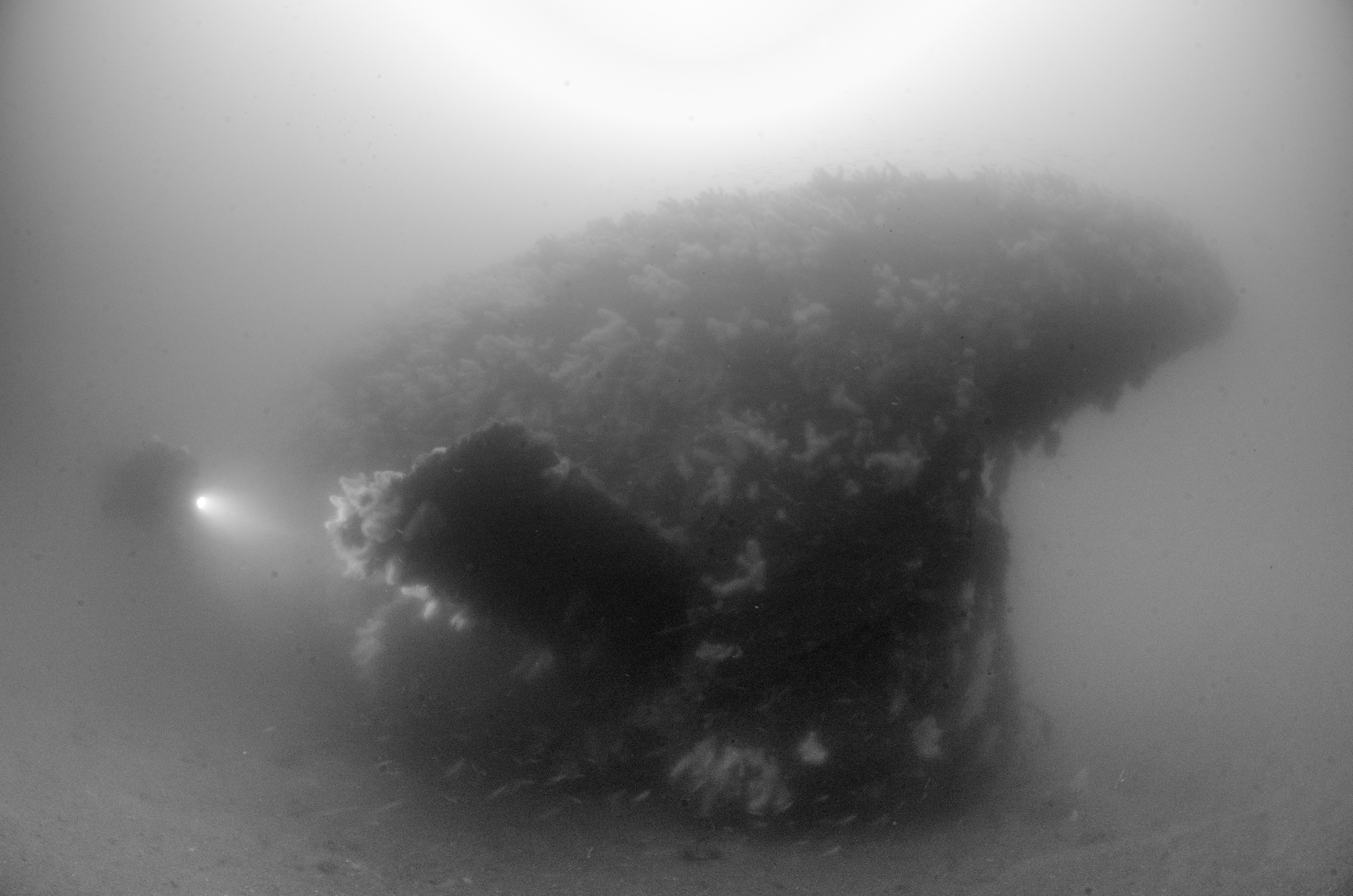

WWI Battle of Jutland Wrecks

The Battle of Jutland was the largest surface naval battle ever, in terms of displacement, and the only full-scale clash of battleships during the First World War. Britain suffered more casualties and lost more ships than Germany, but the outcome was a strategic success for the British since it resulted in the successful containment of the German Imperial Navy’s High Seas Fleet. Of the 249 ships that fought in the Battle of Jutland, 25 were sunk.

HMS Defence. On 31 May 1916, the armoured cruiser HMS Defence, depicted on the painting above, was sunk after being fired upon by a German battlecruiser and four dreadnoughts. Two salvoes from the German ships detonated her rear magazine, and in turn, her secondary magazines. The ship exploded, with the loss of all men on board but one. Between 893 and 903 men were killed and went down with the ship. The wreck is now a designated and protected resting place. Despite its violent demise, it has been found to be largely intact.

HMS Invincible. With an overall length of 567ft (173m) Invincible was significantly larger than her armoured cruiser predecessors of the Minotaur class, the lead ship of her class of three battlecruisers. During the Battle of Jutland, Invincible suddenly appeared as a clear target before German battlecruisers Lützow and Derfflinger, which fired three salvoes each at Invincible and sank her in 90 seconds. The midships magazine exploded, which blew the ship in half—1,026 sailors were killed. The wreck rests on a sandy bottom at a depth of 180ft (55 m).

HMS Queen Mary. HMS Queen Mary was the last battlecruiser built by the Royal Navy before the First World War. The ship never left the North Sea during the war. During the Battle of Jutland, she engaged the German battlecruisers SMS Seydlitz and SMS Derfflinger. A shell from Derfflinger ultimately hit forward and detonated one or both of the forward magazines, which broke the ship in two near the foremast. A further explosion, possibly from shells breaking loose, shook the aft end of the ship as it began to roll over and sink—1,266 crewmen were lost and only 18 survived. Maximum depth is 57m.

SMS Lützow. Lützow was a German battlecruiser, which was heavily engaged during the Battle of Jutland. It was involved with the sinking of the British battlecruiser HMS Invincible and is sometimes given credit for sinking the armoured cruiser HMS Defence. During the battle, she was heavily damaged by heavy-calibre shell hits, which led to the flooding of her bow, and she was in serious danger of capsizing. As a result, the ship was unable to make the return voyage to Germany. Her crew was evacuated, and she was sunk by torpedoes fired by one of her escorts. Depth at her resting place is 43m.

SMS Frauenlob. Frauenlob saw little action during the Battle of Jutland, but in one of the chaotic night engagements as German forces tried to disengage and return home, Frauenlob was hit by a torpedo launched by the cruiser HMS Southampton, which caused the ship to capsize and sink with the vast majority of her crew. The wreck sits upright on the seafloor and is largely intact. Maximum depth is 55m.

Sea War Museum Jutland

Thyborøn is a fishing village on Jutland’s North Sea coast as well as the location of the Sea War Museum Jutland. The museum is one of a kind. The main focus of the museum is the maritime warfare in the North Sea during the First World War, in particular, the “Battle of Jutland.” Visit: Seawarmuseum.dk

In connection to the museum, a memorial park for the Battle of Jutland has been erected in the dunes next to the sea. Visit: Jutlandbattlememorial.com

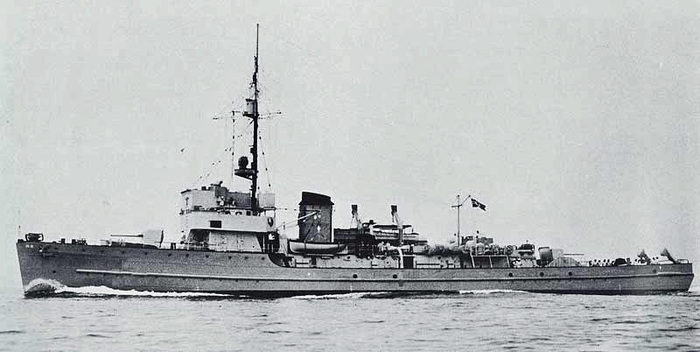

WWII Wrecks

M36 “The Inverted”. The WWII German minesweeper was sunk by British Beaufighter bombers in 1945 and now rests at around 30m at the edge of the deep-water shipping channel. The often strong currents and the intense shipping traffic passing nearby makes this one of the most challenging dives. On a good day, it is one of the most impressive wrecks. It is nearly 100m long and still has its gun turrets, torpedo tubes and machine cannon. The propellors and rudder are also impressive. It lies on its side, hence it is known as “Den Omvendte” (“The Inverted”).

M575. M575 is another WWII German minesweeper but not a casualty of war, as such. She foundered in bad weather on 2 March 1945 after taking on water and before she could make it back to Helsingør, a port at the narrowest point of Øresund. The wreck rests on its port side at a depth of 26m, just north of Helsingborg. Visibility on the wreck varies, and currents can be strong, as it is located in the strait.

M1108 “Dr Eichelbaum”. M1108 “Dr Eichelbaum” was an armed trawler—a fishing vessel converted for naval service. Around the onset of WWII, the ship began service in the German Kriegsmarine’s 11th minesweeping squadron. On 13 April 1940, when it was rammed by the steamer S/S Scandia in Storebælt (Great Belt) and quickly sank with the loss of one sailor. While the wooden wheelhouse (seen in the photo) is no longer there, the rest of the wreck is quite intact and sits upright on the bottom. In front of the bow, a long boom, which was part of the minesweeping equipment, now lies stretched out across the seabed. The hold can be penetrated but be careful because of the accumulated silt. There is a plaque on the deck, in front of the bridge, dedicated to a diver who perished inside. The parts behind the bridge have lots of details, including the now empty davits, which are still in place but missing their lifeboats. Depth is 27m. Currents are usually not strong in this part of the strait.

In the upper right corner (in the above photo), there is a crate with code wheels for an Enigma-coding machine. The Enigma was a top-secret cypher device used by all branches of the German military during WWII. The Germans believed, erroneously, that the Enigma machine was so secure that even the most top-secret messages were enciphered on this device. During the war, British cryptologists, led by Alan Turing, decrypted a vast number of messages enciphered on Enigma. The intelligence gleaned from this source, codenamed “Ultra” by the British, was a substantial aid to the Allied war effort. Several movies, docudramas and documentaries have been produced about these events.

U-251. Type VII U-boats were the most common type of German World War II U-boat. The Type VIIC was the workhorse of the German U-boat force, with 568 commissioned from 1940 to 1945. U-251 was sunk on 19 April 1945 in the Kattegat by rockets and strafing from eight British and Norwegian Mosquito aircraft, with the loss of 39 sailors. Four survived. The location is just southeast of the Danish island of Anholt. The submarine rests upright on the seabed at a depth of 35m. The conning tower has quite visible battle damage, as does the foredeck. A hatch is open and so is a torpedo tube, but penetration is not recommended due to silt inside the submarine. The propellers are still there. Many fish, such as cod, usually congregate around the wreck.

SS Ostmark. A steamer built in France in 1935 and originally named Côte d’Argent, it was commandeered into German service during WWII, equipped with cannons, and renamed SS Ostmark. By 1943, it served as a minelayer. In early 1945, she took part in the evacuation of refugees from the Eastern Front. Sunk by British Halifax bombers on 21 April 1945—109 of the ship’s complement of 240, perished. Caution: The wreck apparently still holds a significant amount of ammunition. Depth is 32 to 45m.

Minos (SS Hellfrid Bissmark). Minos is one of the more popular and most visited shipwrecks. It was a German steamer, which struck a mine in 1939 en route from the German port of Kiel to Malmø, Sweden, with a cargo of nitrate. The shipwreck remains relatively intact, but parts of the superstructure have begun to deteriorate and collapse. It is possible to enter the cargo hold and boiler room. The depth at the location is 27m and is usually not subject to strong currents.

Backgrounder: Battles & Bombardment of Copenhagen

During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century, two major battles took place off Copenhagen, which left several shipwrecks—some with cannons still onboard—just outside the city and in fairly shallow waters.

At the beginning of 1801, during the French Revolutionary Wars that pitted France against Great Britain, Britain’s principal advantage over France was its naval superiority. The Russian Tsar Paul, having been a British ally, arranged a League of Armed Neutrality, comprising Denmark, Sweden, Prussia and Russia, to enforce free trade with France. The British viewed the League to be very much in the French interest and a serious threat.

1801. The first battle fought on 2 April 1801, came about over British fears that the powerful Danish fleet would ally with France. As the British ships closed in on Copenhagen, in whose harbour the Danish fleet was anchored, several Danish ships stationed in the city’s inlet formed a blockade. Most of the Danish ships were not fitted for sea but were moored along the shore with old ships (hulks), no longer fit for service at sea, but still powerfully armed, as a line of floating batteries off the eastern coast of the island of Amager, in front of the city in the King’s Channel (a shipping lane leading to the port).

The Danish fleet defended the capital with these ships and bastions on both sides of the harbour inlet. Eventually, the battle swung decisively to the British, as their superior gunnery took effect. The Danish agreed to the British terms upon hearing news of the death of the Russian tsar, as it meant they could cut their ties with the French without fear of retaliation by Russia.

Of the Danish ships engaged in the battle, two had sunk, one had exploded, and twelve had been captured. As the British could not spare men for manning prizes, as they suspected that further battles were to come, eleven of the captured ships were burned.

This was not to be the end of the Danish-Norwegian conflict with the British. In 1807, similar circumstances led to another British attack, in the Second Battle of Copenhagen.

1807. Despite the defeat and loss of many ships in the First Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, Denmark-Norway (possessing Jutland, Norway, Greenland, Schleswig-Holstein, Iceland and several smaller territories) still maintained a considerable navy.

Faced with the prospect of Napoleon defeating Russia and Prussia, which would lead to French control of Baltic fleets, the British felt compelled to take action and pre-empt the substantial Danish navy from siding with the French. Although ostensibly neutral, Denmark was under heavy French pressure to pledge its fleet to Napoleon. Britain also had valuable trading interests in the Baltic, which was a vital source of naval supplies.

In early August 1807, a British expeditionary force, comprising more than 400 warships and transports carrying more than 29,000 troops, reached Danish waters and demanded that the Danes allow their fleet to be taken into British control. The Danes refused, and hostilities began.

The British landed an army in Zealand, which invaded Copenhagen, and on 2 September, began a fierce bombardment of the city after the Danish king refused to surrender his fleet. The bombardment included 300 Congreve Rockets, which caused fires. Due to the civilian evacuation, the normal fire fighting arrangements were ineffective; over a thousand buildings were burned. Soon, much of the city was in flames, and the Danes, suffering heavy civilian casualties, were forced to surrender on 7 September.

Denmark agreed to surrender its navy and its naval stores. In return, the British undertook their departure of Copenhagen within six weeks. On 21 October, the British fleet left Copenhagen for the United Kingdom.

Age of Sail wrecks

Kanonvraget (Cannon Wreck). This wreck lies at a depth of only nine to 12 m of water, which is often above the thermocline. Thus, it is often in winter, when there is little planktonic algae, that one gets the best visibility. Despite its position in a busy strait, the wreck was not located until 2002. The identity of the wreck has not yet been established. The ship is estimated to have been approximately 48m long, and due to the 16 large 12 to 14-pounder iron cannons that now lie scattered about on the wreck, the Swedish archaeologists who found the wreck assumed it was from the First Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. However, according to Danish marine archaeologists, there are no vessels from this battle known to have wrecked in the middle of the Sound. Another theory has it that it is the frigate Charlotte, which foundered in 1737, in about this location, but her length is believed to have been 36 to 40m, and armed with six-pounder cannons, so it is probably not her either.

Fløyte Træ Vrag (Dutch Fluyt). The fluyt was a dedicated cargo vessel designed by the Dutch in the 16th century to maximize available cargo space; it was cheap to build and could be handled by a small crew. This vessel probably sank during the Great Northern War (1700–1721) only 2.5km from the port of Helsingør and the narrowest point of Øresund. The wreck, which lies at a depth of just 16m, was only located in 1994. It has probably only become exposed in recent times and is now at risk of being broken down and consumed by shipworm.

Sværdfisken (The Swordfish). The wreck is also known as “Kanonprammen,” which loosely translates to “The Cannon Barge.” It was part of the line of defence during the battle of 1801. Its armament comprised eighteen to twenty 24-pound cannons. The barge was commanded by second-lieutenant S.S. Sommerfeldt, as it came under fire from HMS Edgar and HMS Ganges. It burnt and sank in a position north of Flakfortet, a sea fort located on the artificially built island of Saltholmrev in Øresund, between Copenhagen and Saltholm. The wreck re-emerged after the construction of the Øresund bridge and tunnel link between Copenhagen and Malmö, Sweden, which probably caused currents and sand to shift about.