Battle of Jutland Centenary Expedition

It is hard to put into words what I was feeling at this stage. I was descending the shot line in approximately 15m visibility and an image started to appear. Not the random wreckage you often see, or even the straight lines of a cargo ship, instead these were two long barrels. This was no ordinary wreck—I was looking at the ‘X’ Turret of HMS Invincible.

Contributed by

Diving the shipwrecks of the Battle of Jutland had always been an ambition of mine. Having first learnt about the battle at school, it had always resonated with me—hundreds of ships, mighty platforms speeding in excess of 20 knots, firing their enormous guns and, of course, the human tragedy of over 8,000 lives lost.

Twice before had our UK deep wreck diving team, Darkstar, attempted to get to the site, but a combination of bad weather and mechanical problems had so far thwarted our plans. In mid-September 2015, however, a discussion with Mark Dixon, who leads the dive team and owns the project’s 12m long catamaran (also named Darkstar), started a plan that would take nine months to execute. Not only would we once again try for Jutland, but we would do it on the 100th anniversary, and lay a wreath in memory of the sailors who perished over the two days of the battle on 31 May and 1 June 1916.

Getting there

Taking the catamaran to the site was the first leg, and a challenge in itself. Mark and I took the boat over from the Royal Quays in North Shields to Thyborøn on the Jutland peninsula in Denmark, via West Terschelling in Holland—a journey that took over 24 hours. Sailing through the darkness of the North Sea at night is not for the faint-hearted. We may as well have been in a room with black shutters, only occasionally alleviated by a light in the distance. However, we were blessed with calm seas and the passage proved uneventful.

On arrival, the rest of the team had already reached the destination, having driven to Thyborøn via the Channel Tunnel. All good so far—except for the wind—and boy, did she blow! I have heard of Jutland expeditions sitting in harbour for four weeks and managing only three days of diving—but surely, not this time?

The waiting around did allow us time to visit the new Sea War Museum Jutland in Thyborøn (opened in September 2015) and become involved in the opening ceremony of the Jutland Memorial Park. May 31 was a no-go; the wind did not abate and we were left kicking our heels. Then, 100 years to the day of the second day of the Battle of Jutland, the weather calmed and we headed out at last. Our destination was to be the closest wreck to the port, a mere 75 miles to the final resting place of HMS Invincible.

HMS Invincible

Invincible was the first battle cruiser built anywhere in the world. Built at Armstrong Whitworth on the Tyne and launched in 1907, it weighed 17,250 tons and was 173m in length. By the time of the Battle of Jutland, the ship had already taken part in the Battles of Heligoland Bight and the Falkland Islands, having played its part in the sinking of the German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

Under the command of Admiral Hood, Invincible was the flagship of the Third Battlecruiser Squadron at Jutland. At approximately 6:30 p.m. on May 31, the ship came under intense fire from the Derfflinger and Lutzow. A shell penetrated ‘Q’ turret, which in turn led to a detonation in the magazine, and possibly igniting ‘A’ and ‘X’ turrets. The ship broke in half, its stern and bow sticking out of the water. With 1,026 lives lost, there were only six survivors.

Like most divers, I had dived wrecks with loss of life before. That these wrecks were grave sites was a constant thought in the back of my mind as we swam around "enjoying" the hobby that modern techniques and equipment give us. This experience, however, was on a whole different scale. Each turret had approximately 70 crew members working on them, and I was looking at their last resting place before I even reached the wreck.

On arriving at the turret, in approximately 50m of water, it was immediately clear that an explosion must have also taken place here, as the roof was missing, presumably blown out as the fire ripped through the magazines. Swimming to the back of the guns, I found the breeches closed and locked—a clear indication that artillery was loaded and ready to fire when the fateful salvos came from the ship’s German counterparts. Were the guns still loaded, I wondered, or would the shells have erupted as part of the cataclysmic explosion that tore this once mighty warship in two?

Dropping down from the turret to the wreck itself, a vast array of twisted metal soon revealed itself. Moving forward, a number of smaller, 4-inch guns lay strewn about the ship, as were there small ammunition lying concentrated in one area, while some of the larger shells still lay near ‘X’ turret.

The distinctive Yarrow boilers soon came into sight as we swam towards the upturned bow—a long swim! As impressive as all these features were, however, the most poignant finds were the human elements: small ceramic pots, plates, knives and forks and, perhaps—the most moving of all—the sole of a leather shoe.

All too soon, it was time to head up. Once back aboard Darkstar, we placed a wreath in the water in memory of those lost and as a tribute to their sacrifice. We headed back to shore in a mood that was both sombre and elated.

SMS Frauenlob

The next morning, our nemesis, the wind, returned. Forecasts, however, told us that by midday it would start to back off. So, as morning turned to afternoon, we gingerly pointed our bows out to sea in what could best be termed "questionable" conditions. Our target this time was the German light cruiser SMS Frauenlob.

Sometime after 10:00 p.m. on 31 May 1916, the Frauenlob got involved in a firefight with the British Second Light Cruiser Squadron of HMS Southampton, Dublin, Birmingham and Nottingham. At approximately 10:35 p.m., the Southampton fired a torpedo and Frauenlob sank soon after taking 320 officers and crew members with it—there were only nine survivors.

For over four hours, we battled against 2m swells, as we headed out to the Frauenlob’s final resting place. Arriving on site, a discussion took place as to whether the conditions were, indeed, diveable, and a consensus was reached: It was time to go.

Heading down the shot line, the visibility soon deteriorated. As I reached the wreck itself, it was soon evident that this was not going to be a dive similar to the one the previous day. Visibility was at best at 1 to 2m, and that was being charitable! On top of that, the swell was still evident at the bottom, which, no doubt, played its part in churning up the muddy seabed.

At this stage, I would love to tell you of all the interesting sections on the Frauenlob, but the visibility was just too bad. Moving along the edge of the wreck, it was obvious that, unlike the Invincible, Frauenlob was reasonably intact. Gauges and pipes seemed to indicate that we were in the vicinity of the engine room and heading aft, but that was as much information as I could glean from the dive.

Upon surfacing, conditions had slightly improved. But time was getting on, so we soon headed back to port. With a good forecast from here on in, we looked forward to diving more of these iconic wrecks. Alas, it was not to be!

HMS Queen Mary

The next day, as we headed out to the site of HMS Queen Mary, we were treated to bright sunshine and flat, calm seas. Less than half a mile out of harbour, it was clear that something was not right. Mechanical gremlins had struck the boat down, and we headed back to port—our diving was over for the week.

Fast forward a month. The boat, still in Thyborøn, was now repaired and needed bringing back. So why not go out for the week and try and finish off what we started? It seemed too good an opportunity to miss. Starting from where we had left off, we now headed out to HMS Queen Mary again.

Queen Mary was the pride of the British Fleet. The last battle cruiser built before the outbreak of World War I, Queen Mary was the sole member of its class. At 214m long and 26,700 tons, the ship’s four shafts could produce 28 knots.

During the battle, the vessel came under fire from SMS Seydlitz. But it would be shells from SMS Derfflinger that would cause the detonation that sealed the Queen Mary’s fate. The ship disappeared below the waves at 4:26 p.m., with the loss of 1,266 officers and crew members.

Queen Mary is quite a different dive from the Invincible. Split into two sections, we were diving on the stern, which lies upside down—the thick, armour-plated sides descending to the seabed. However, it is not the upturned keel, as you would normally expect, that first catches the eye.

There have been rumours for years that some of the Jutland wrecks have been illegally salvaged and, at the section we arrived at, there was clear evidence of this. The keel and metal plating had been ripped open, as if by a mechanical grab, exposing the innards of the ship, revealing massive piles of enormous shells and cordite.

Moving forward, we came to the remains of the engine room. Parts of the boilers were missing, and condensers and other parts of machinery lay exposed. More wreckage lay strewn amongst the seabed, though it was unclear whether this was due to the explosion or the subsequent salvage.

HMS Defence

The wind blew for another couple of days. However, this was soon to be forgotten. The forecast for Friday was the best of the week, so we were determined not to waste it. A 3:30 a.m. start saw us heading for what must be one of the most memorable dives in the world—HMS Defence.

Launched in 1907, Defence was the last armoured cruiser built for the Royal Navy. At 14,600 tons, the ship was a little over 158m along. Under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot, Defence led the First Cruiser Squadron. When the wounded SMS Wiesbaden was spotted, Defence opened fire. However, at 6:05 p.m., Defence was spotted by Derfflinger and four battleships at only 8,000 yards. At 6:20 p.m., it was reported that Defence disappeared in a massive explosion, with the loss of all hands, reported to be between 893 and 903 souls.

The shot was on the seabed, on the starboard side of the ship. Contrary to the reports of the time, Defence was relatively intact. Swimming up to the deck level, the immediate impression was gun turrets and more turrets—barrels still at an angle trained on a foe that had left the scene 100 years ago.

Swimming up to the deck, I saw that the original wooden decking was still in place but it had caved in towards the centre. Inside the turrets, shells were stacked, still waiting to be loaded into the breeches. Passing the engine room, I saw that the engines were exposed, with gauges all still in place.

Bow and stern were both blasted off the main wreckage, but also still in place. Moving back onto the main body of the wreckage, the human element was once again evident, with plates and bottles lying amongst the wreckage. By far, this was the most intact of the Jutland wrecks we had visited and a must-see for anyone who manages to get out to the site.

The day, however, was not done, as we undertook a second dive, with a return to HMS Invincible. Once again, I was faced with the massive turret that had started this adventure, a month earlier. It was a fitting way to end our expedition.

Besides myself and Mark, divers Duncan Keates, Ric Waring, Rich Stevenson, Kieran Hatton, Barry McGill and Steve Burke were assisted by Paul Mee on deck. It was a trip that would live long in the memory.

For myself and Mark, however, the trip was not quite over. As the other guys headed off on a 15-hour drive home, Mark and I pointed the bows to North Shields, England. Some rough seas and heavy rain, mixed with calm seas and sunshine greeted us over the next 33 hours, but we finally docked home, safe and sound.

And, we are already planning our return! ■

Published in

-

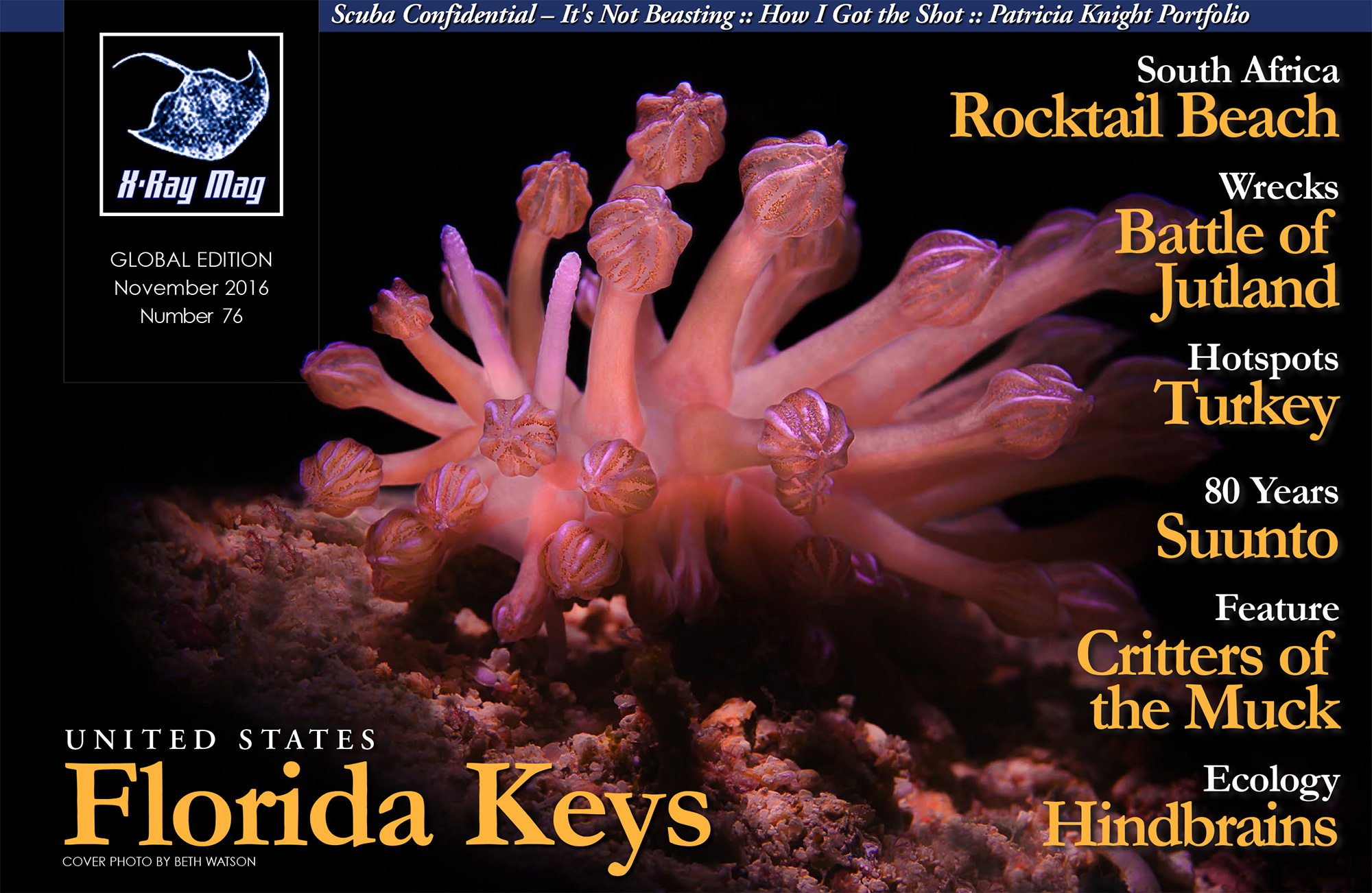

X-Ray Mag #76

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #76

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer